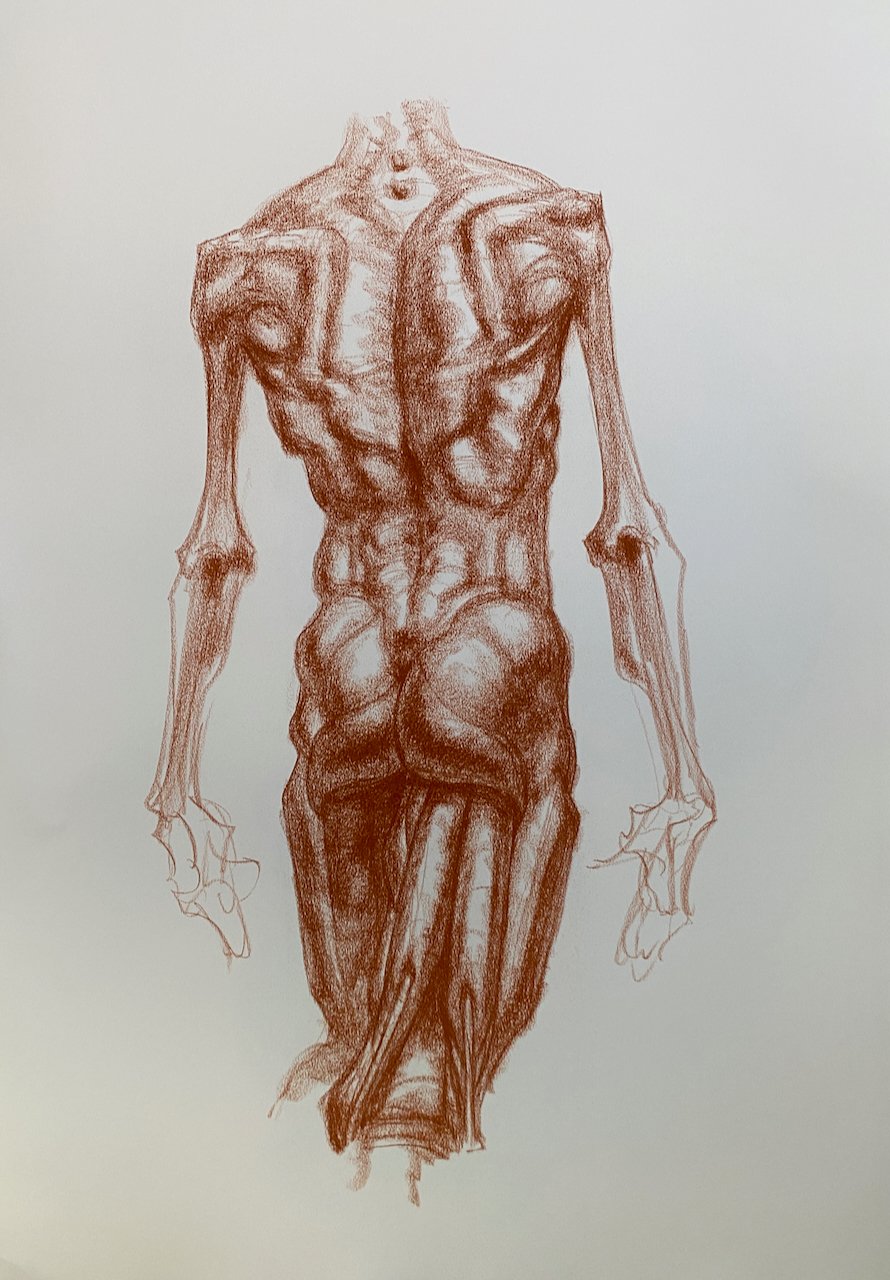

Écorché: The Anatomy of Spirit and Form

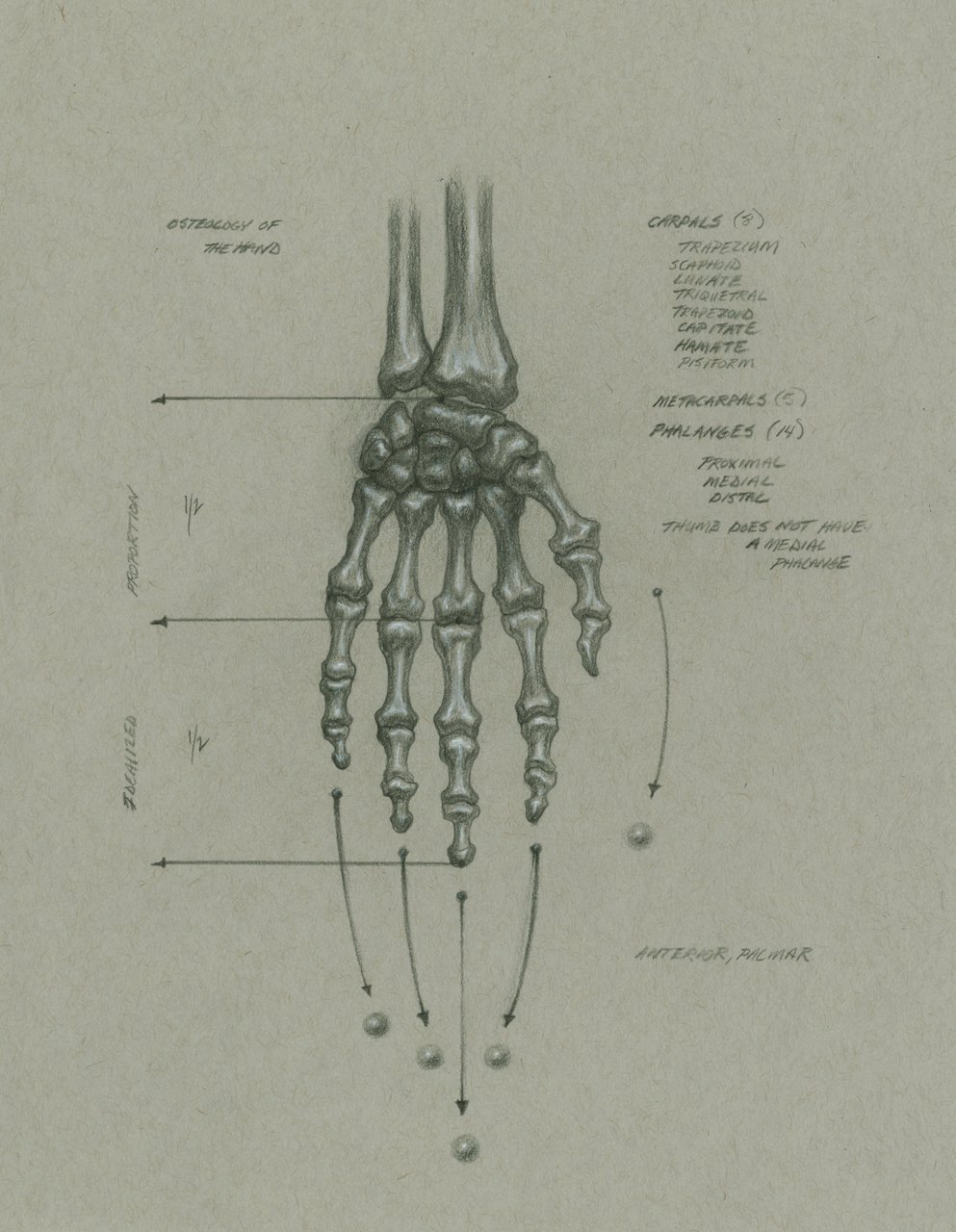

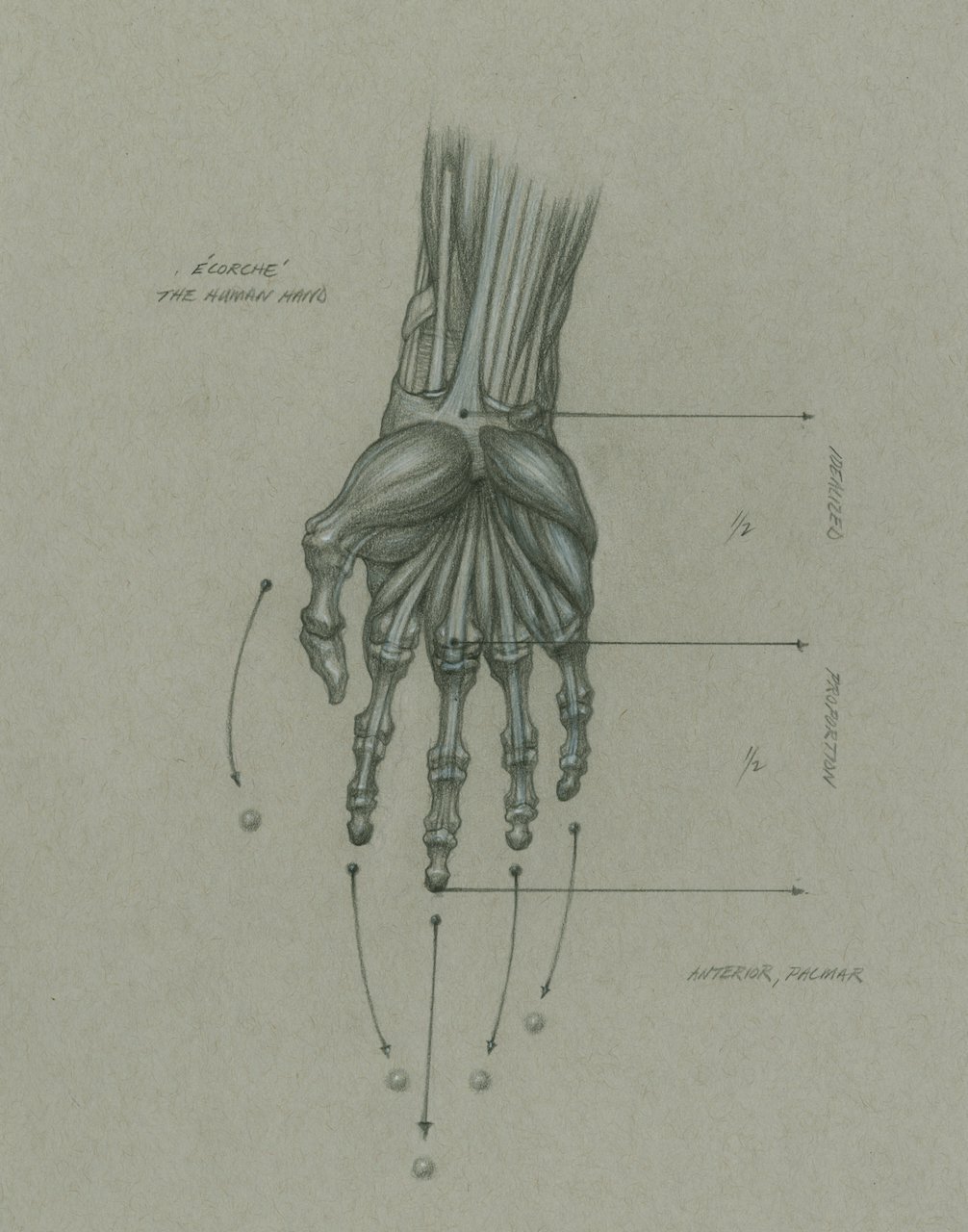

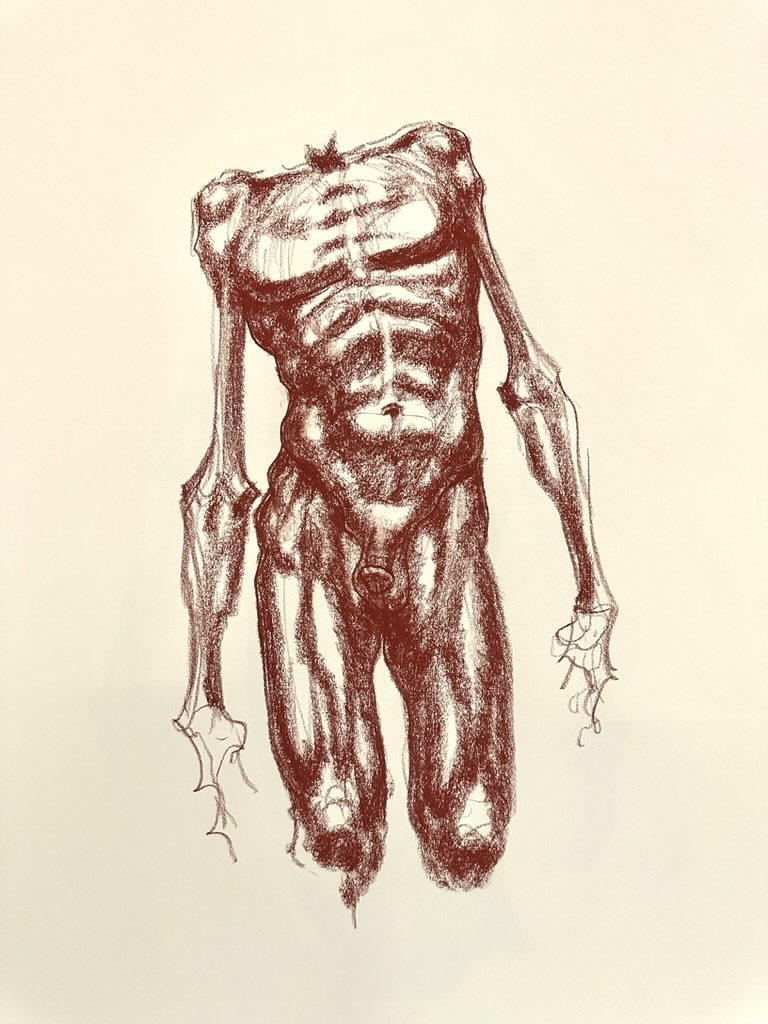

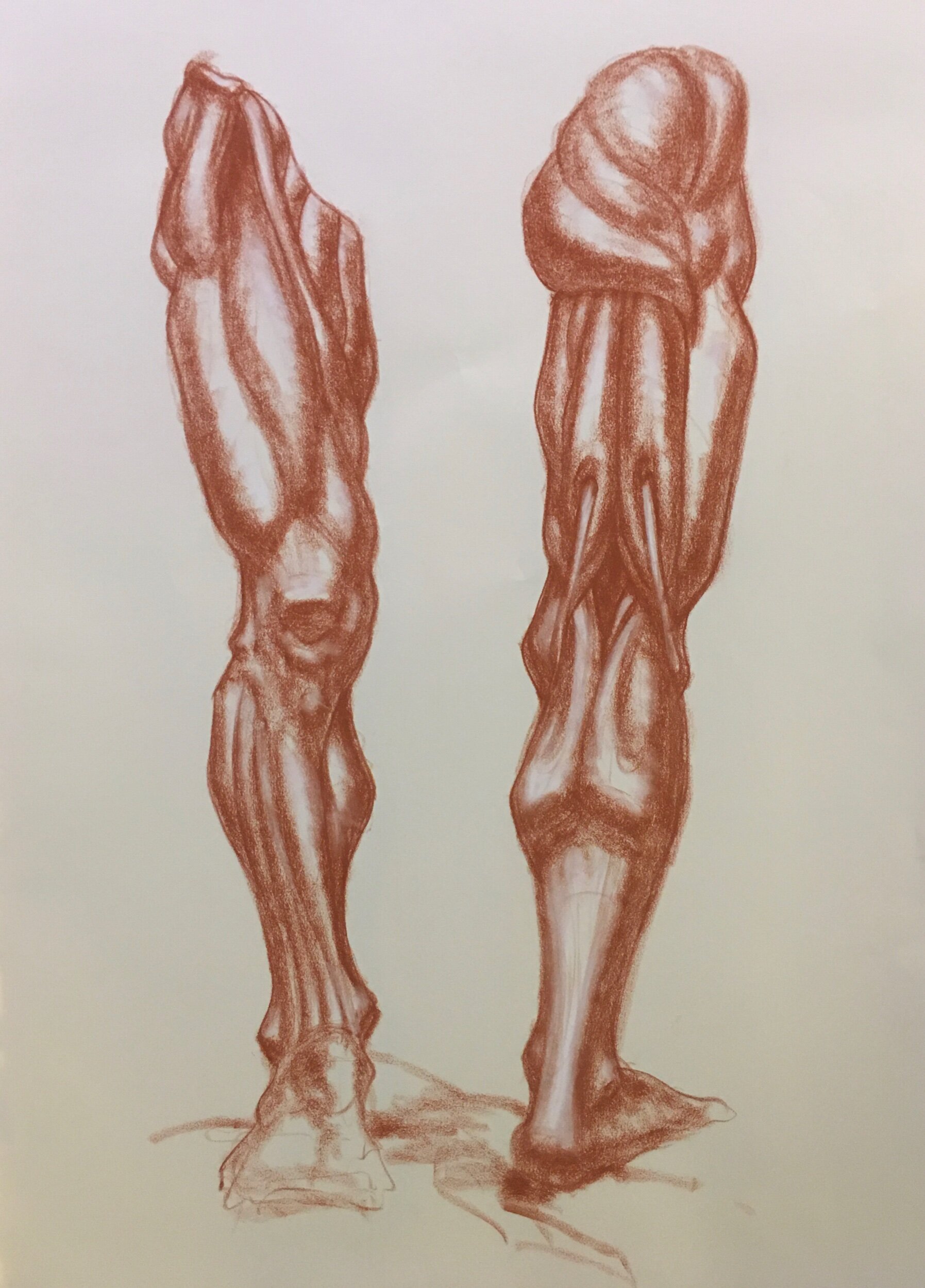

Écorché (pronounced ay-kor-SHAY) is a French term meaning “flayed.” In the context of art and anatomy, an écorché refers to a figure, either drawn, sculpted, or painted, depicted without skin, revealing the underlying musculature of the human or animal body.

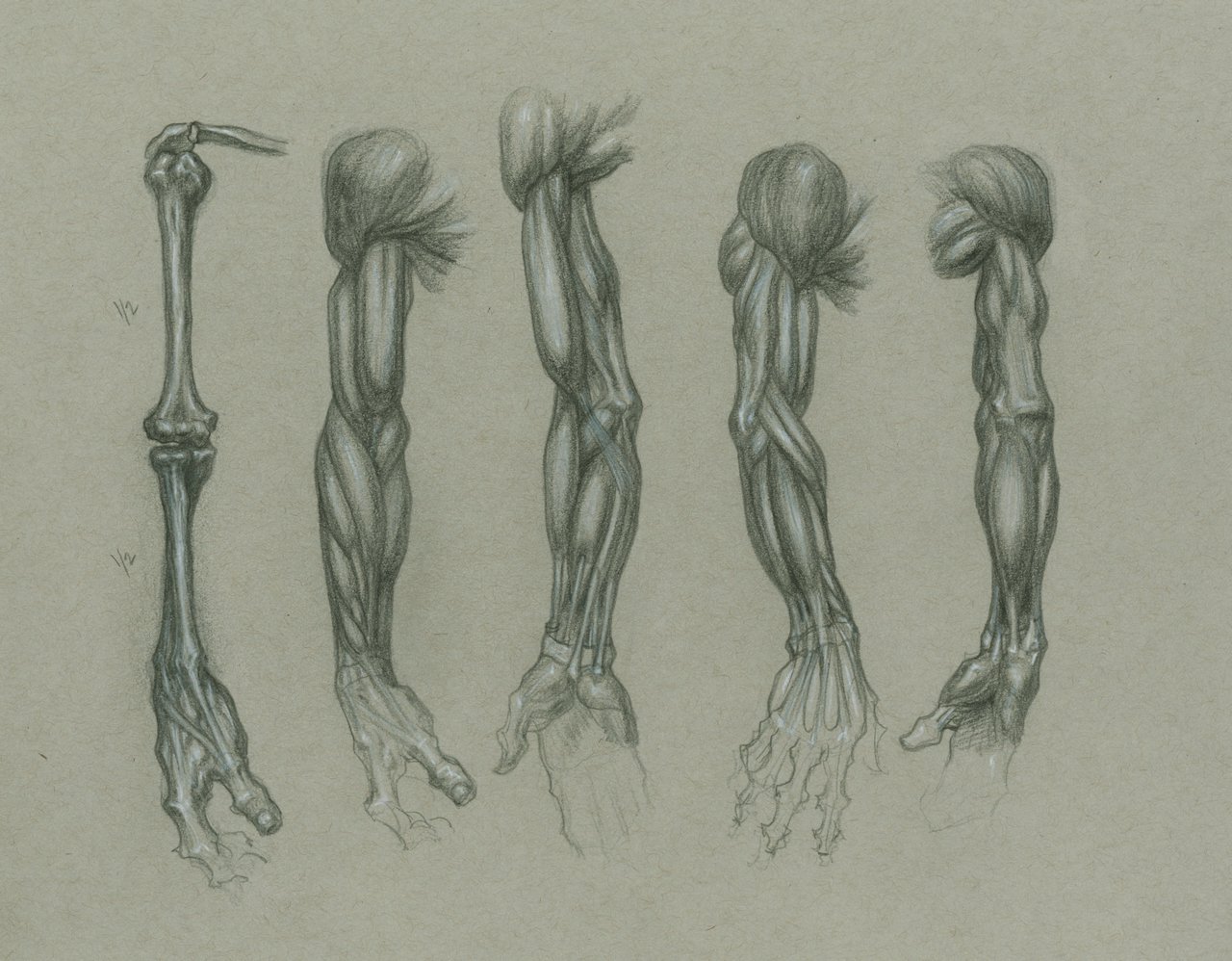

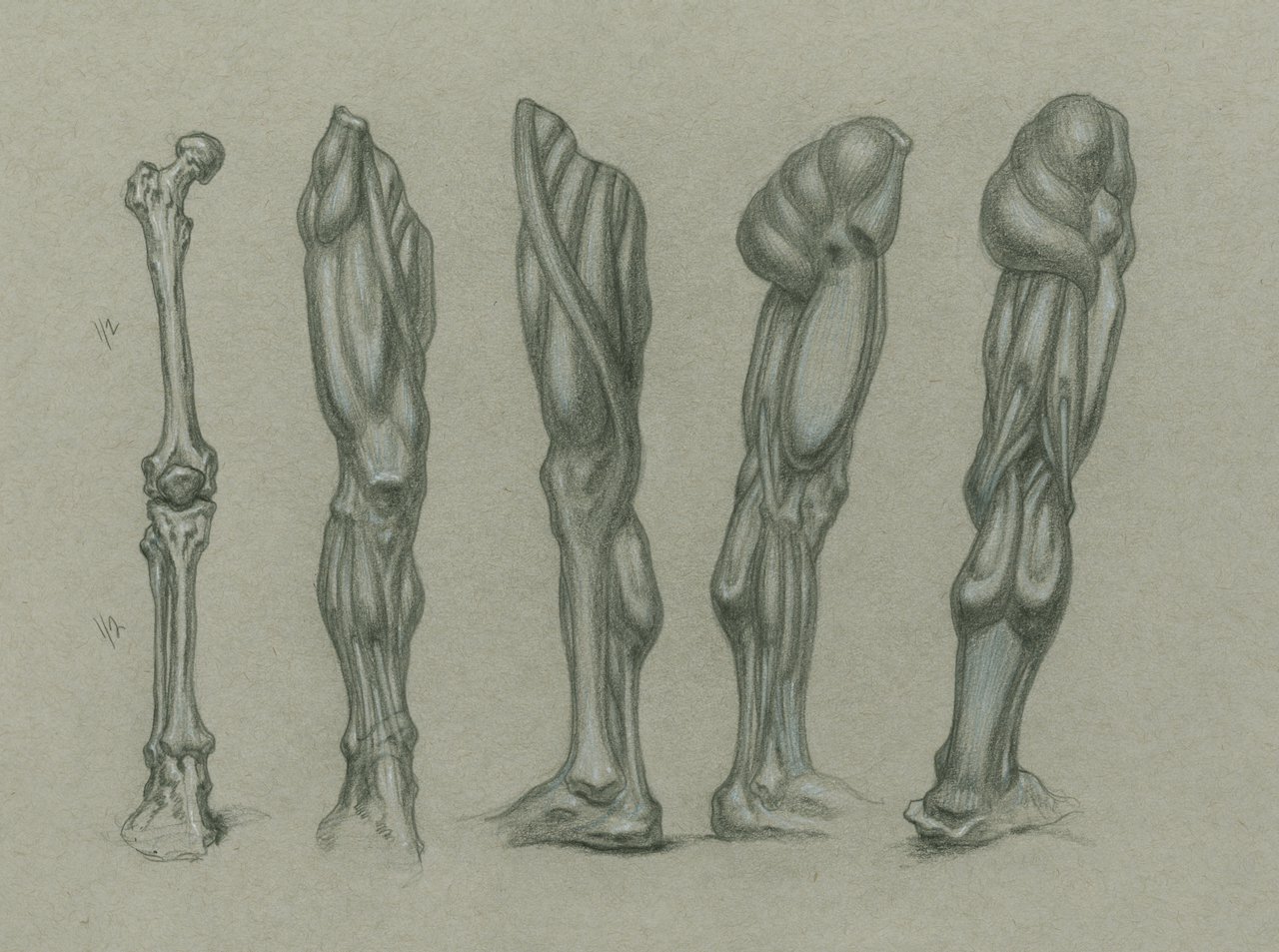

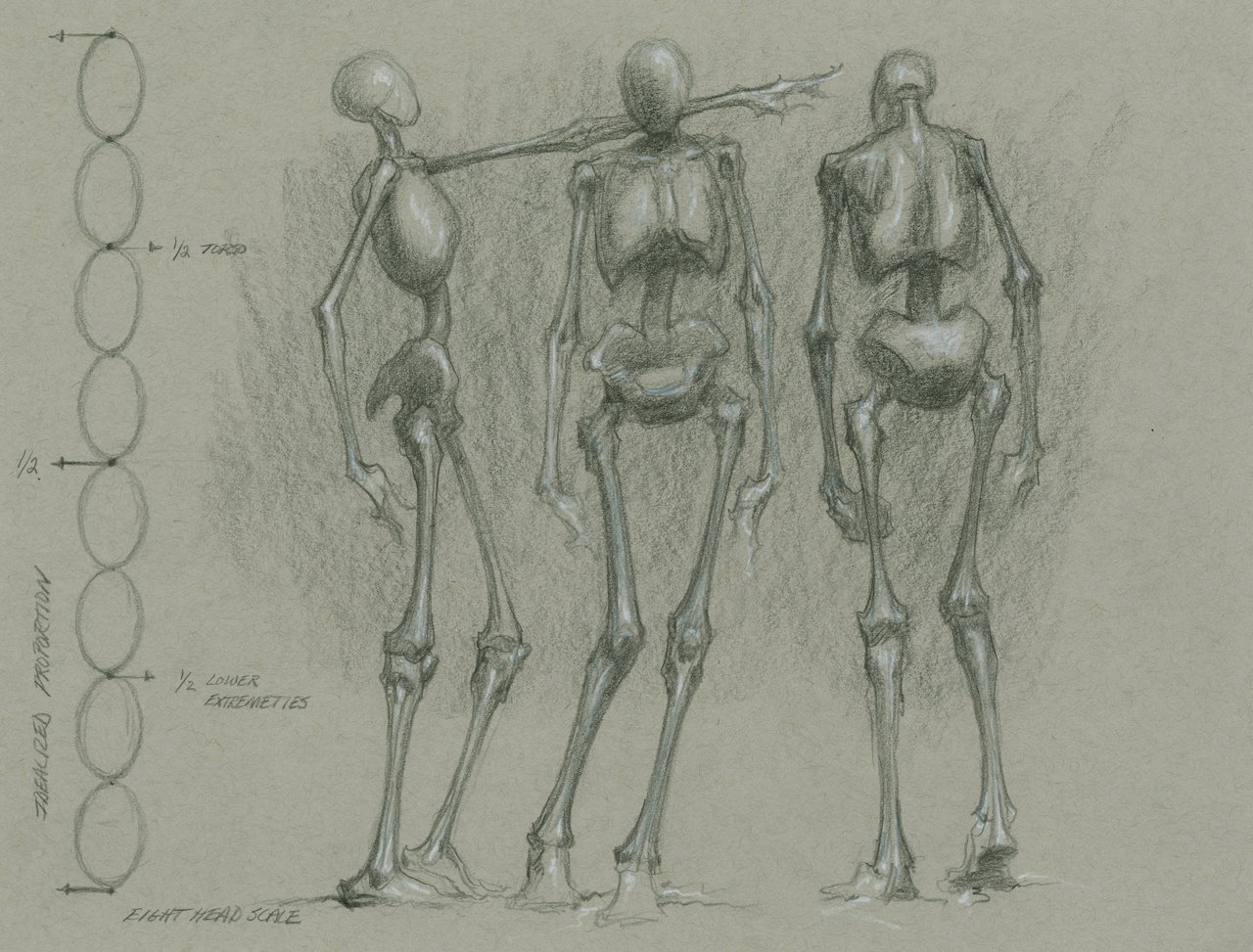

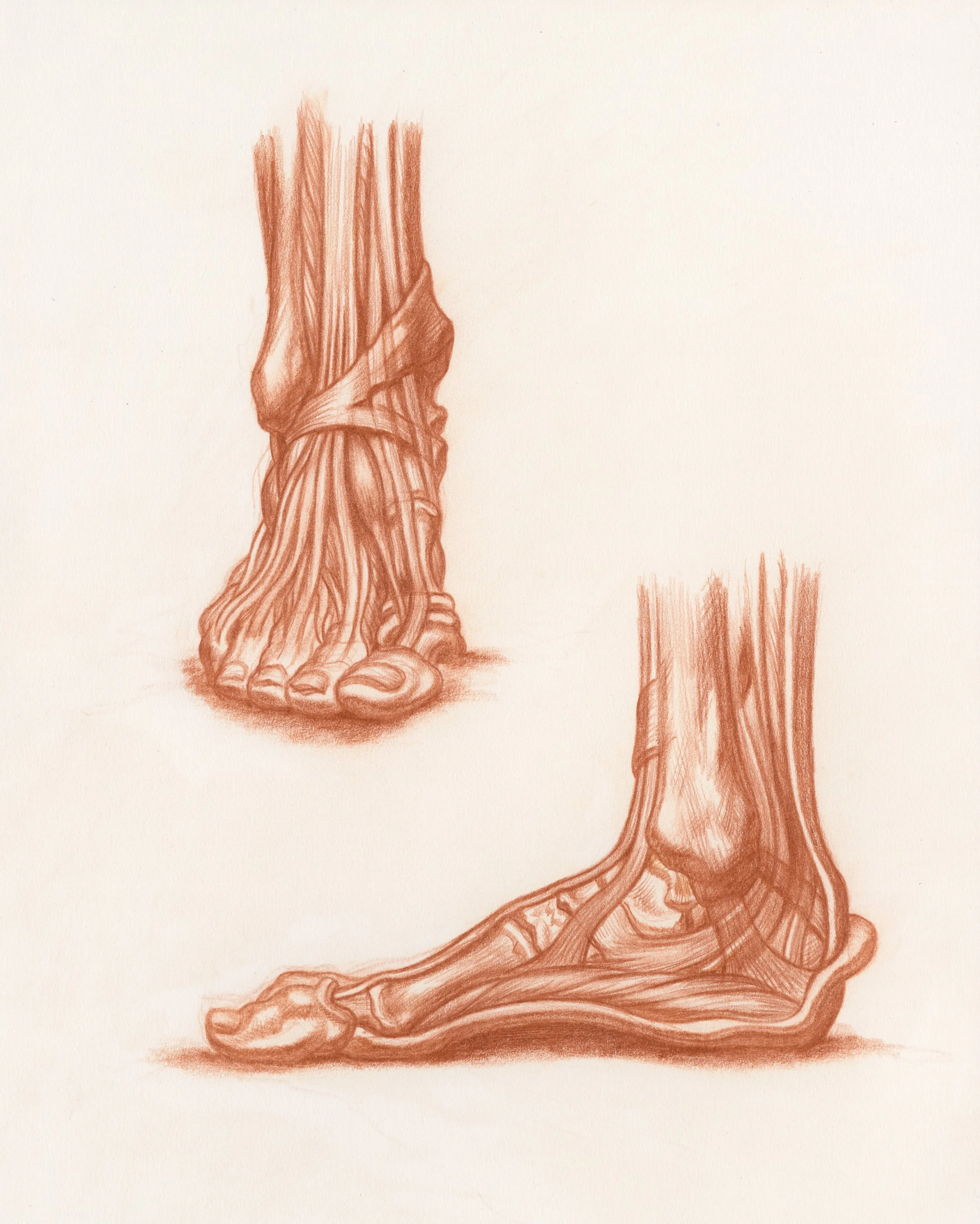

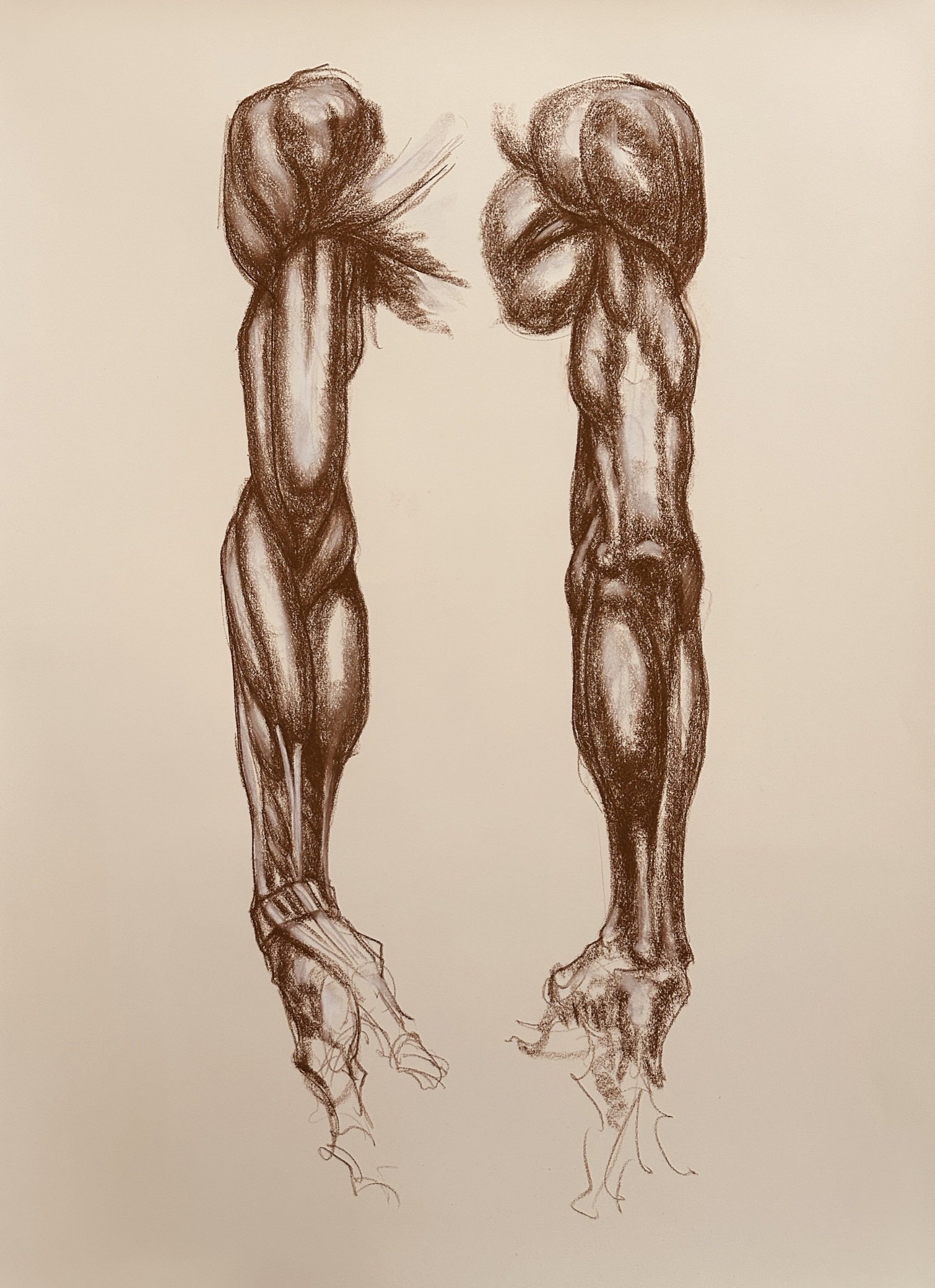

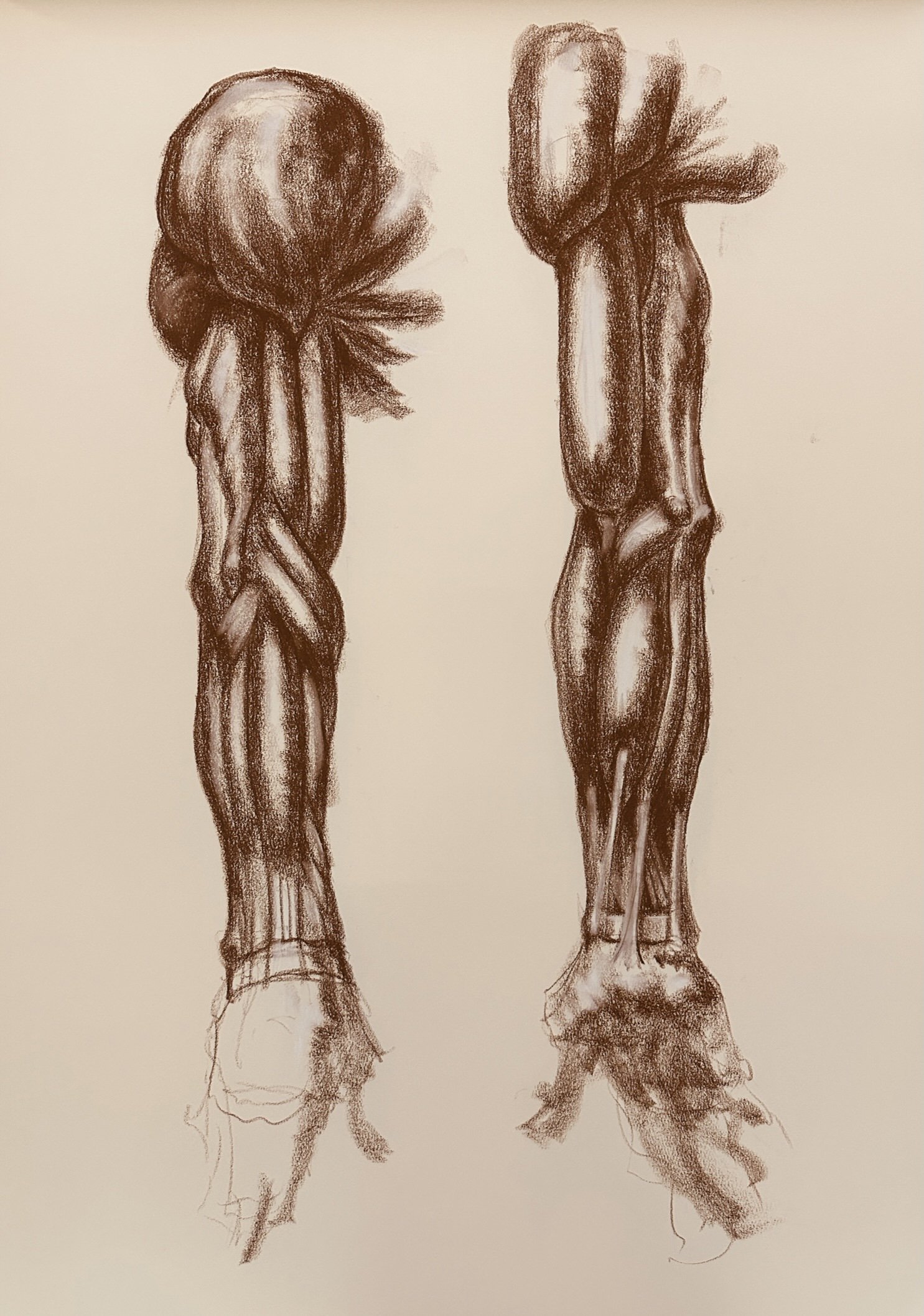

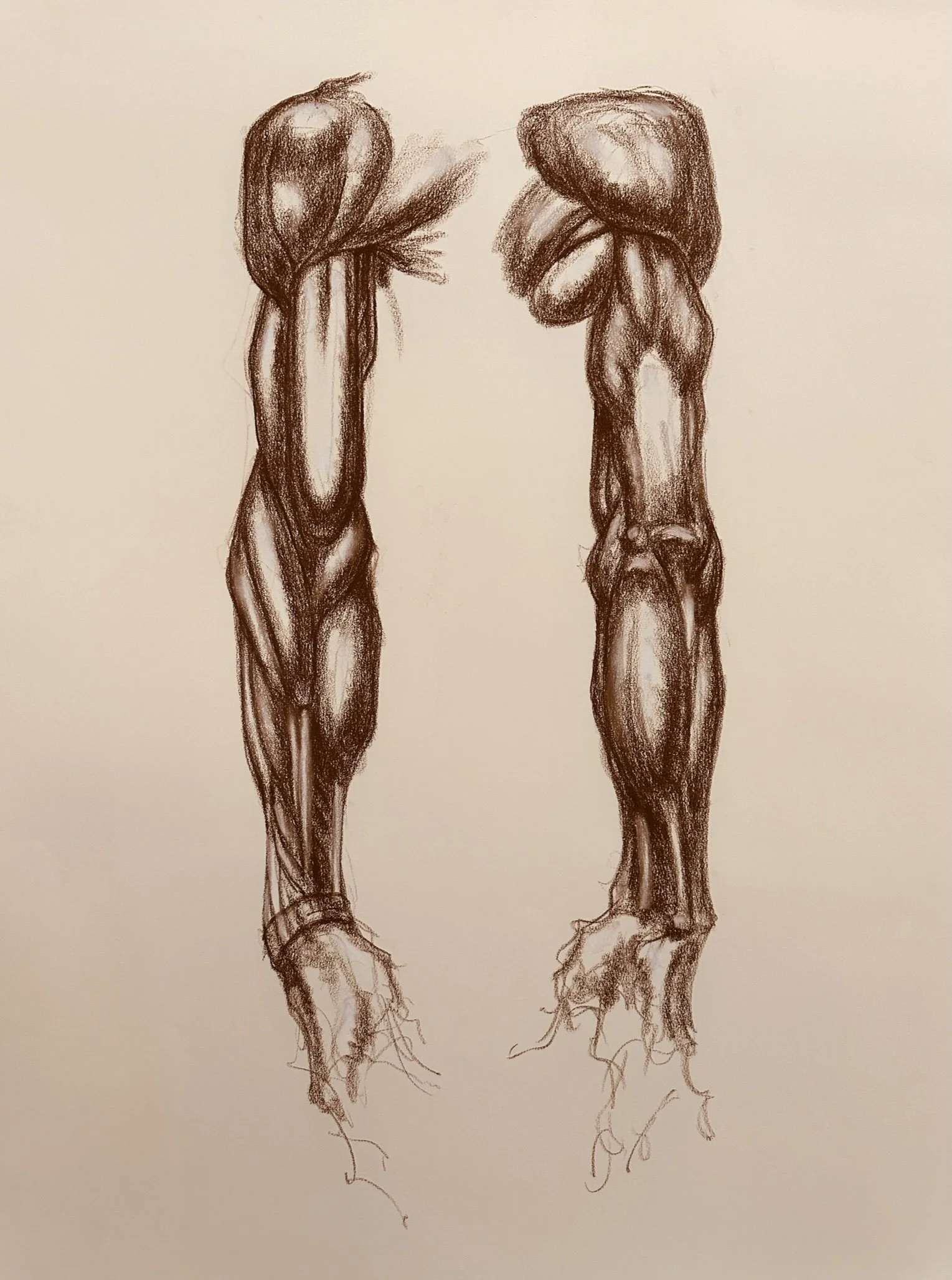

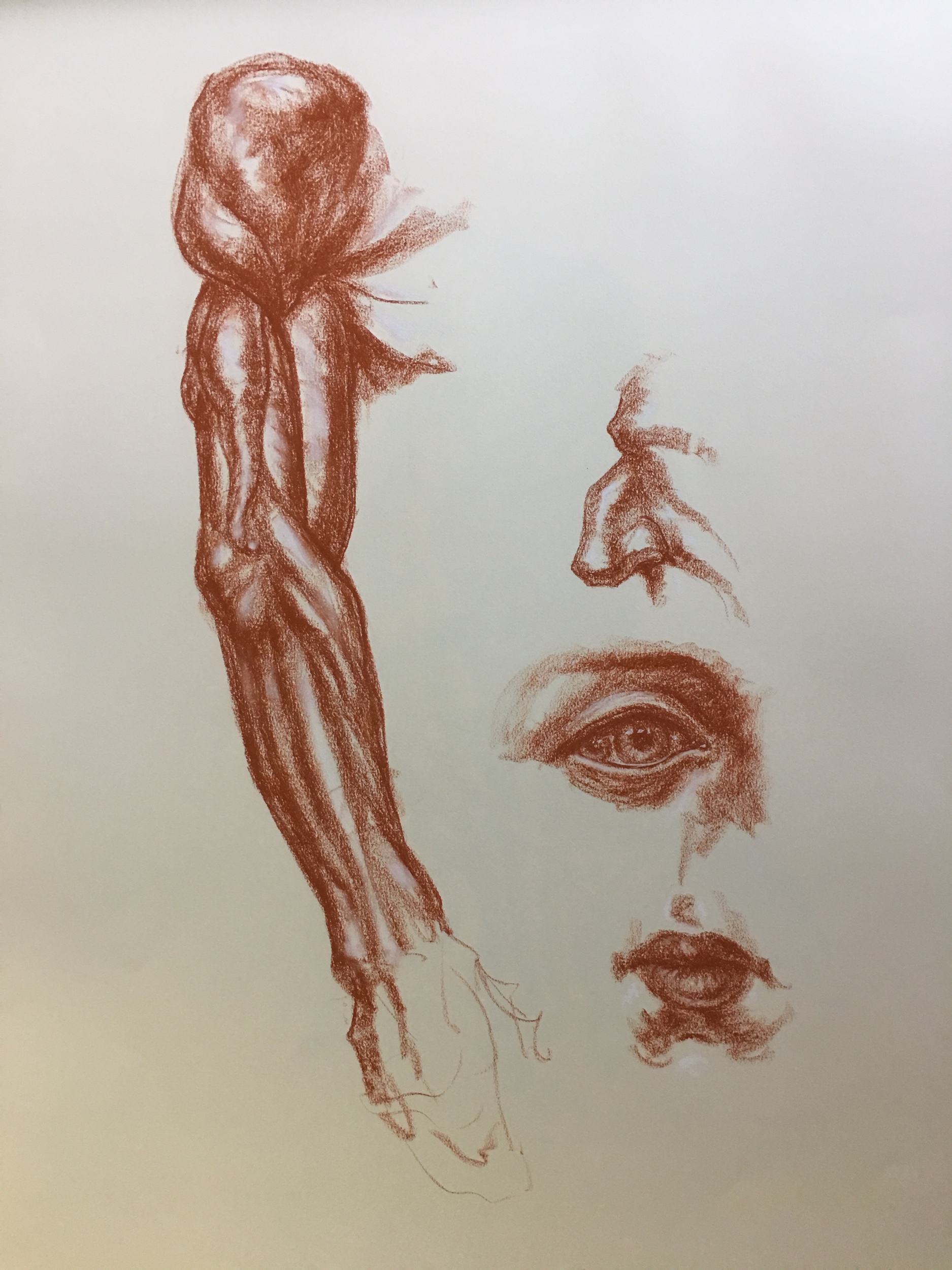

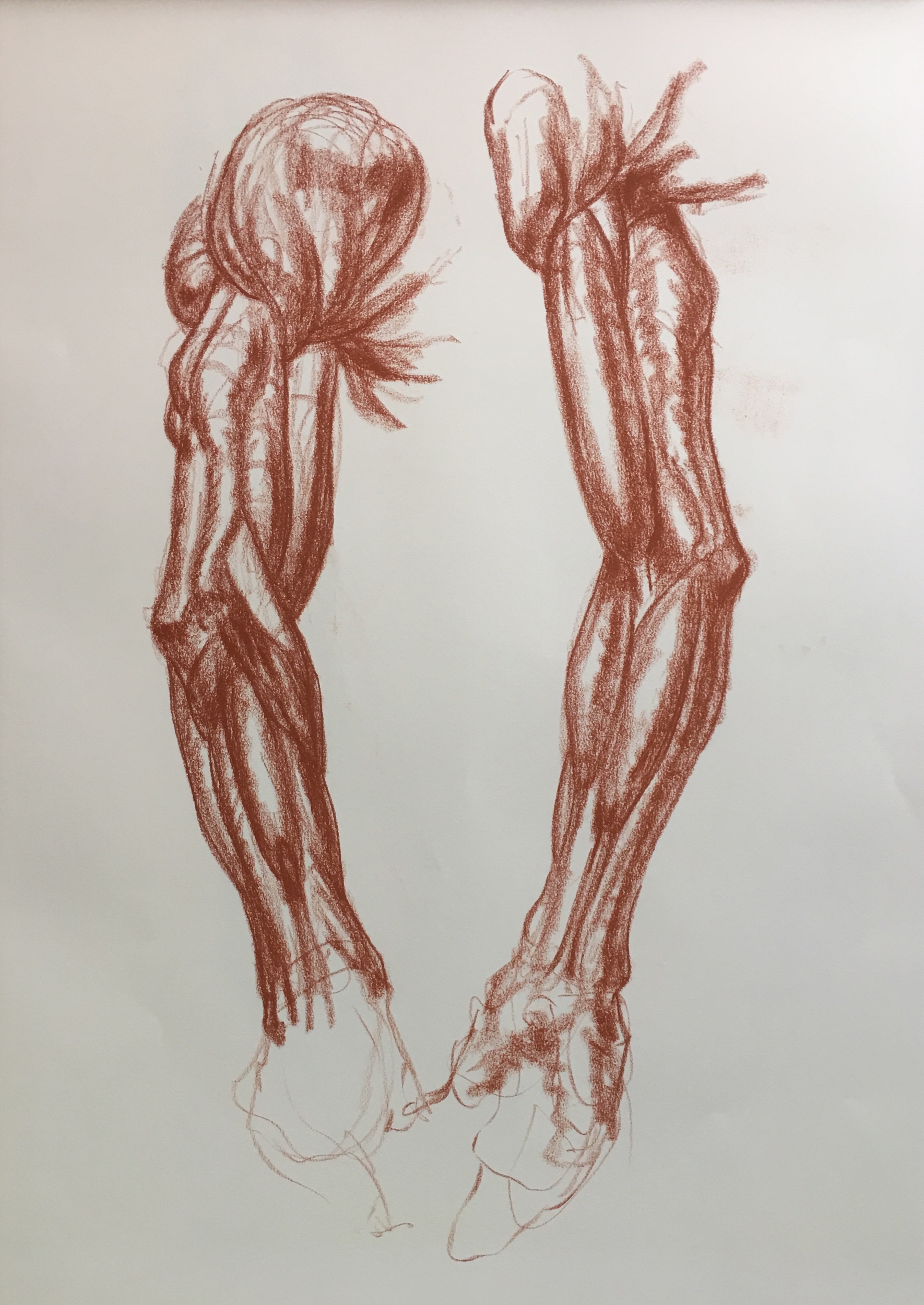

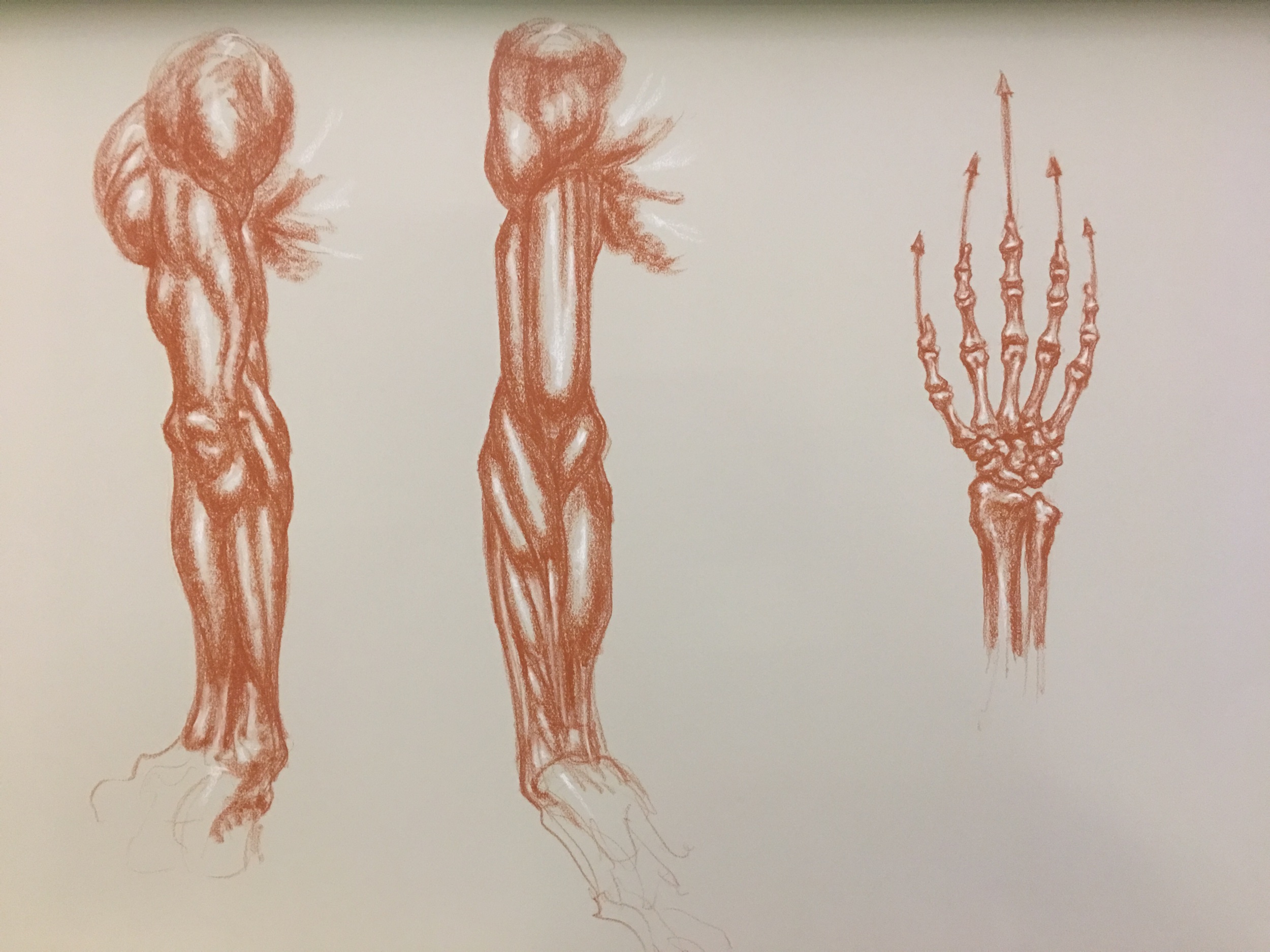

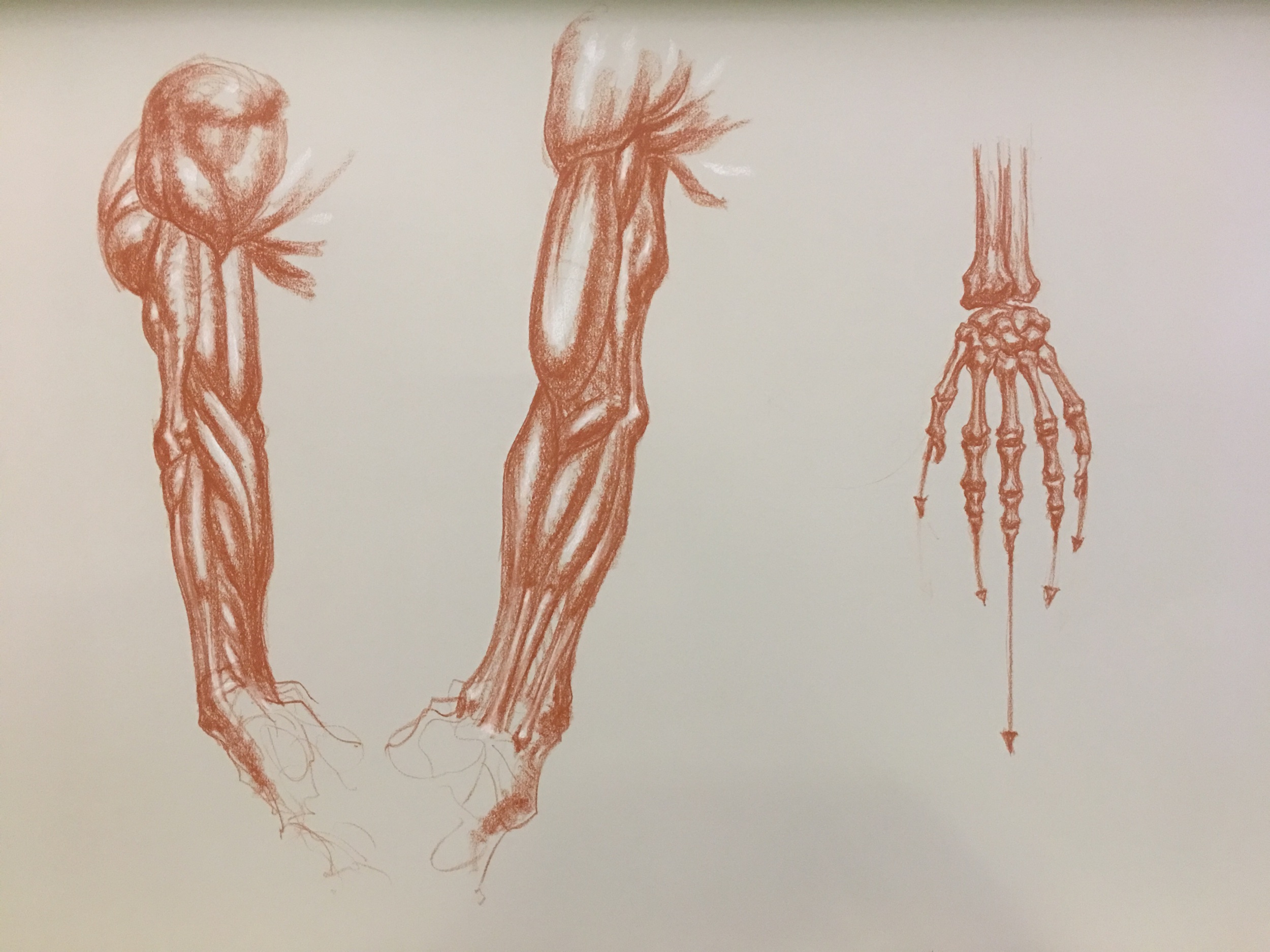

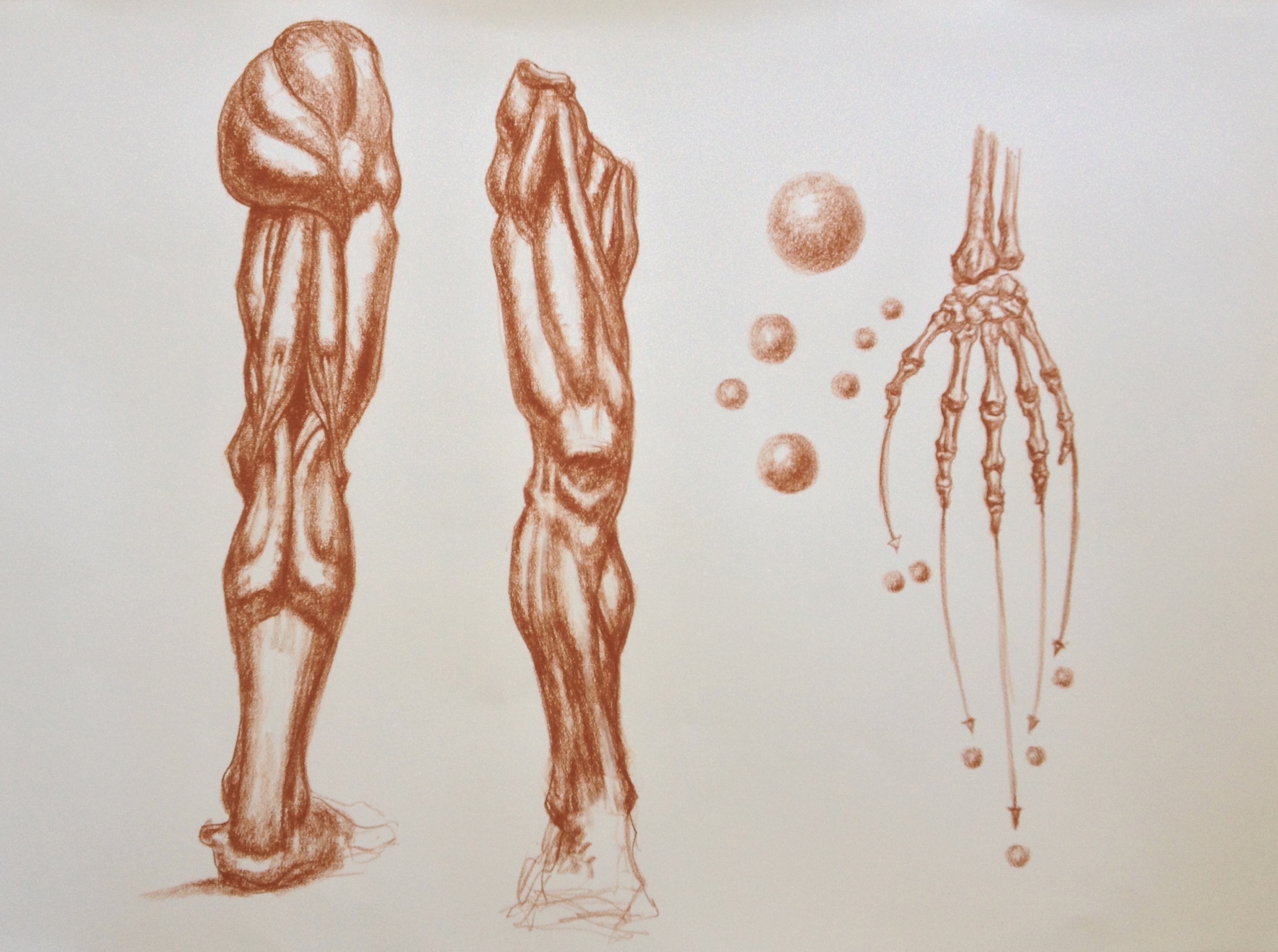

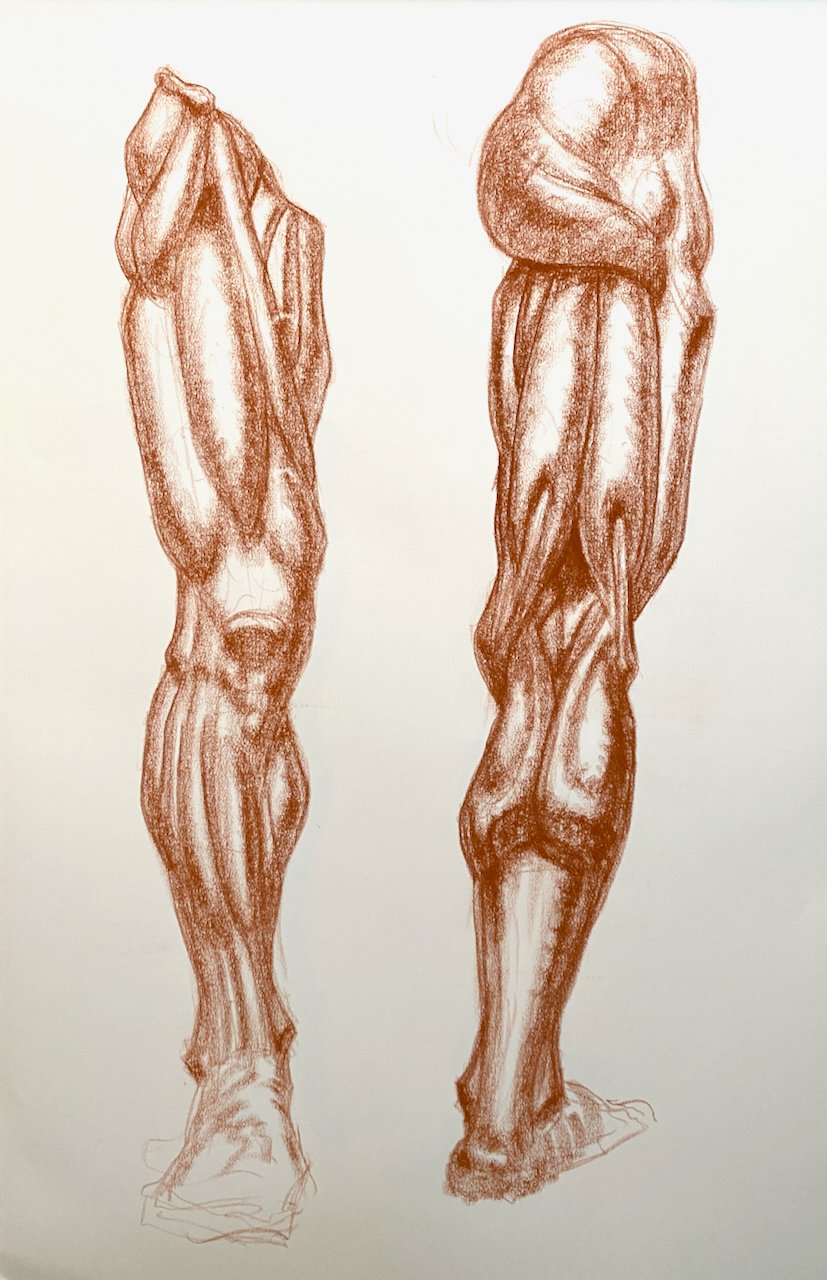

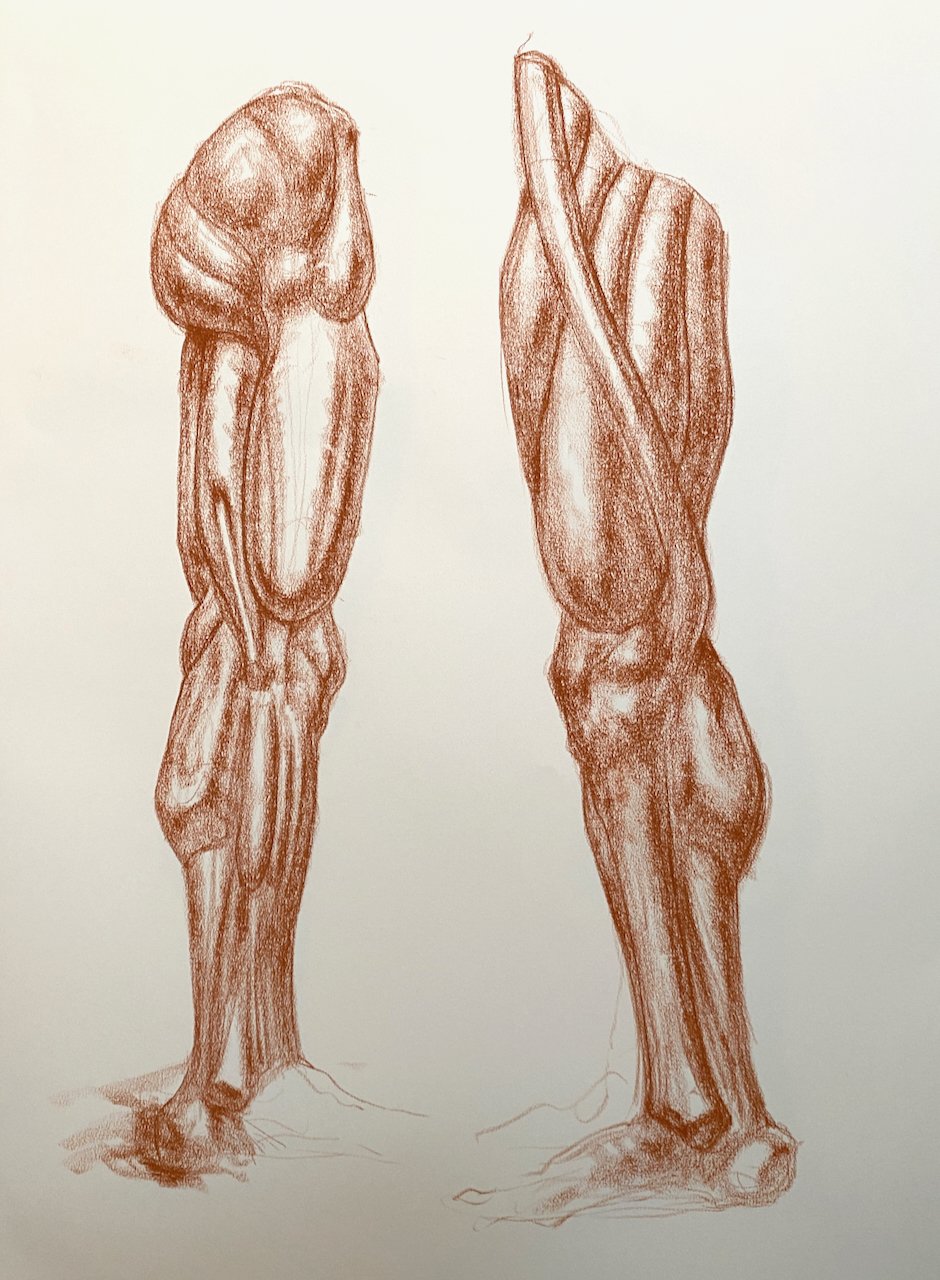

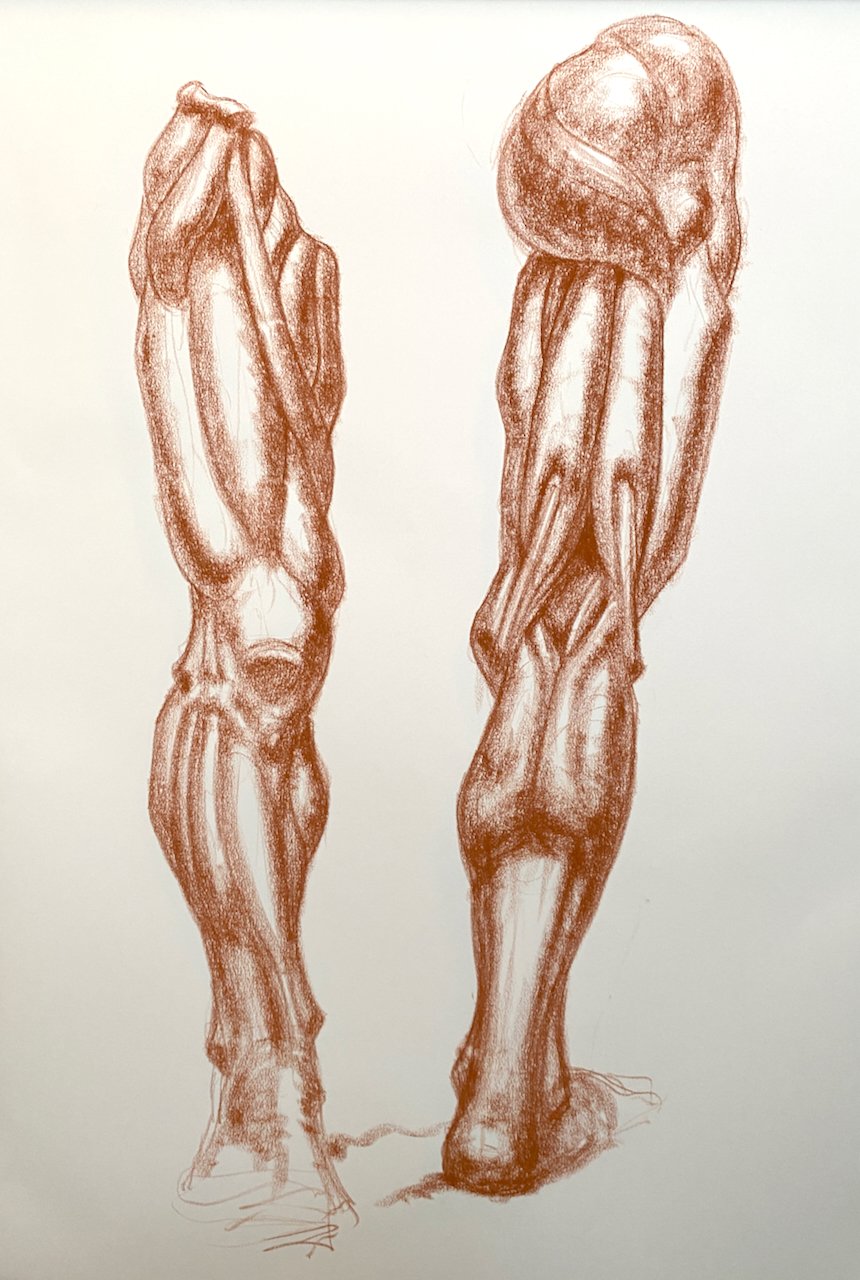

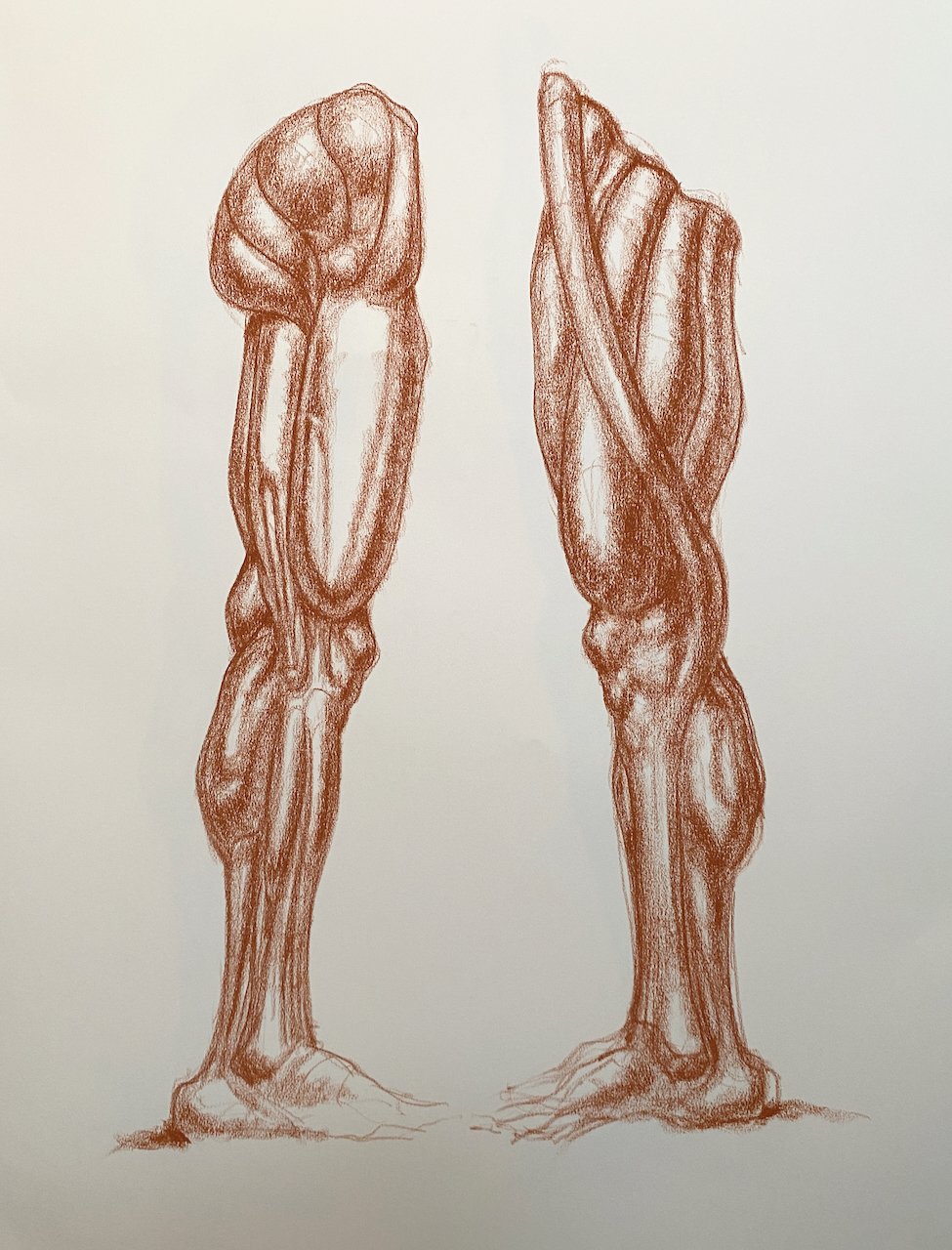

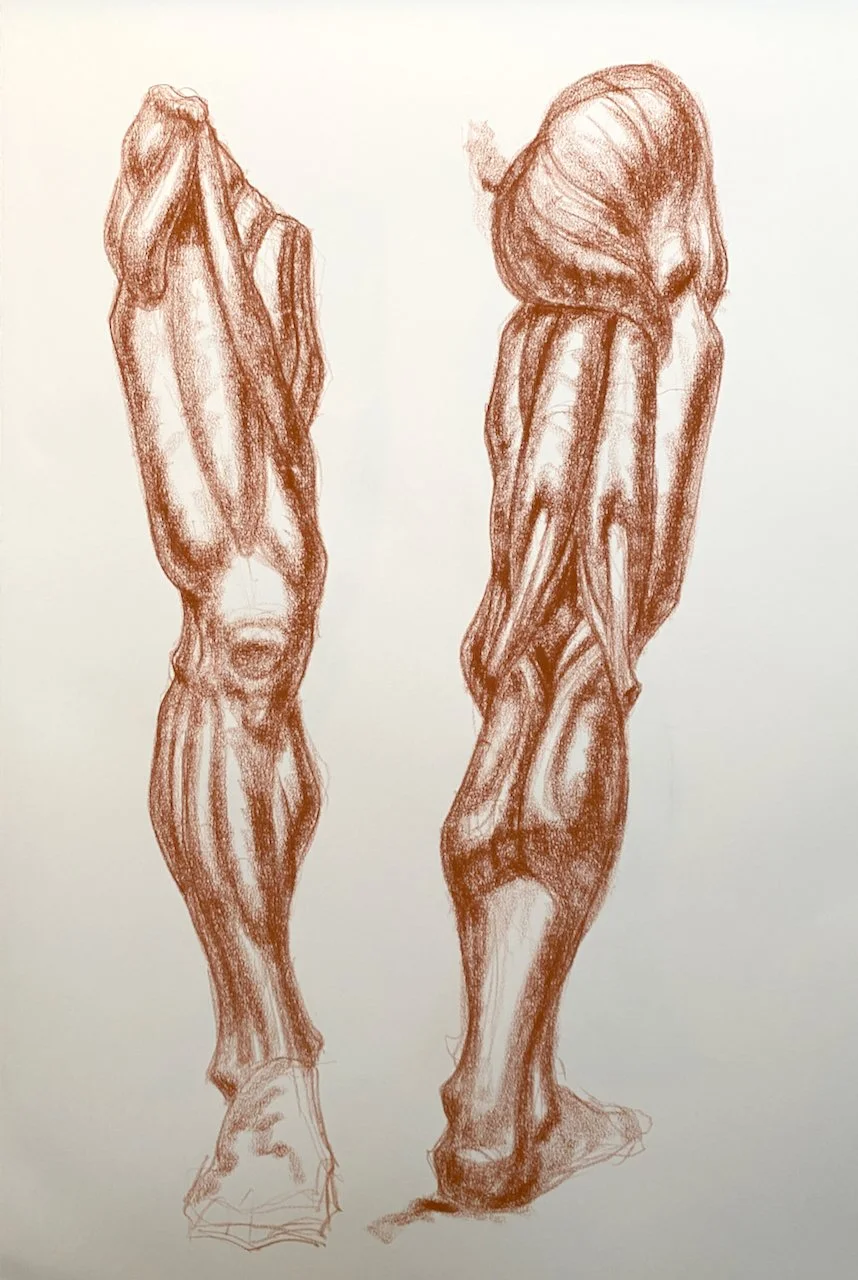

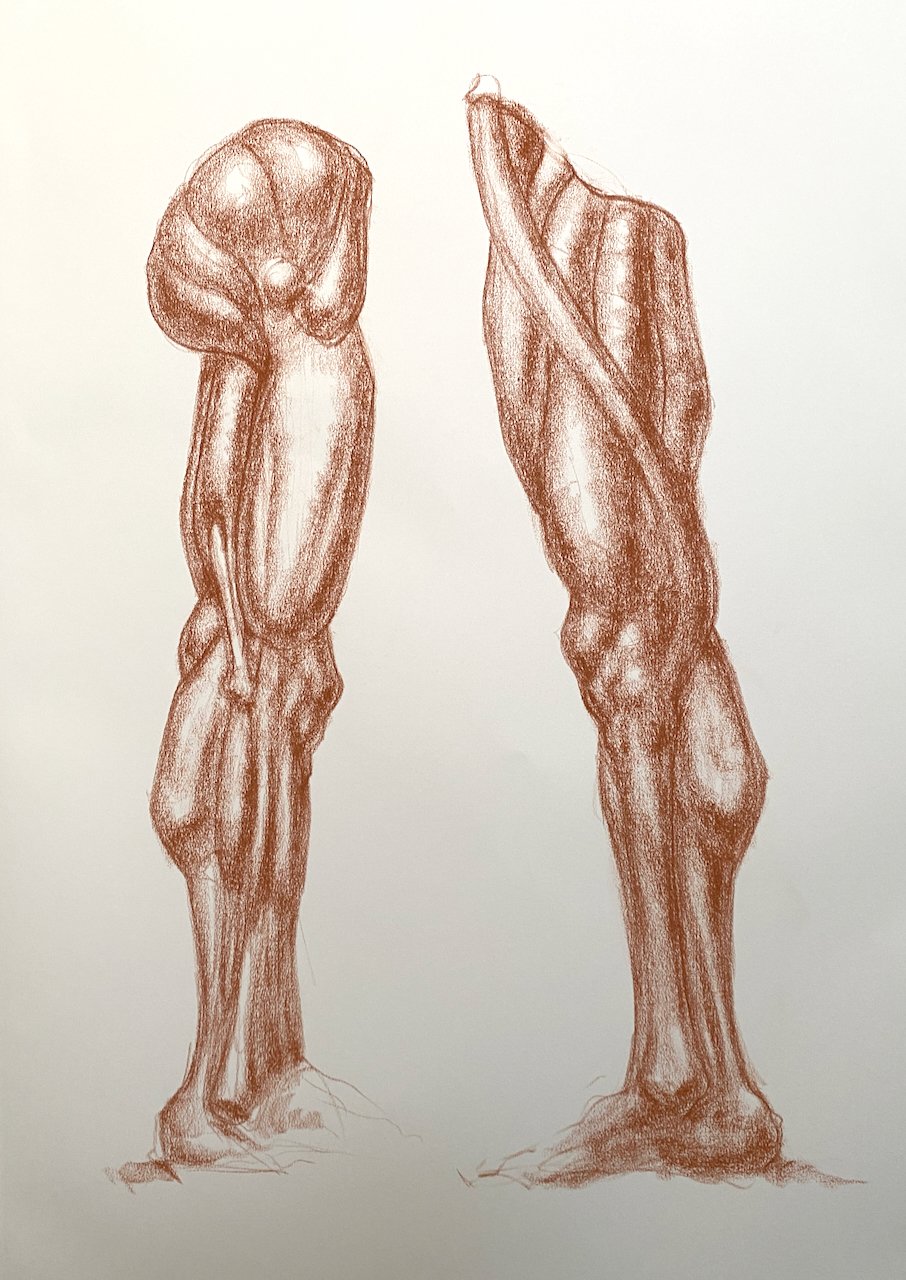

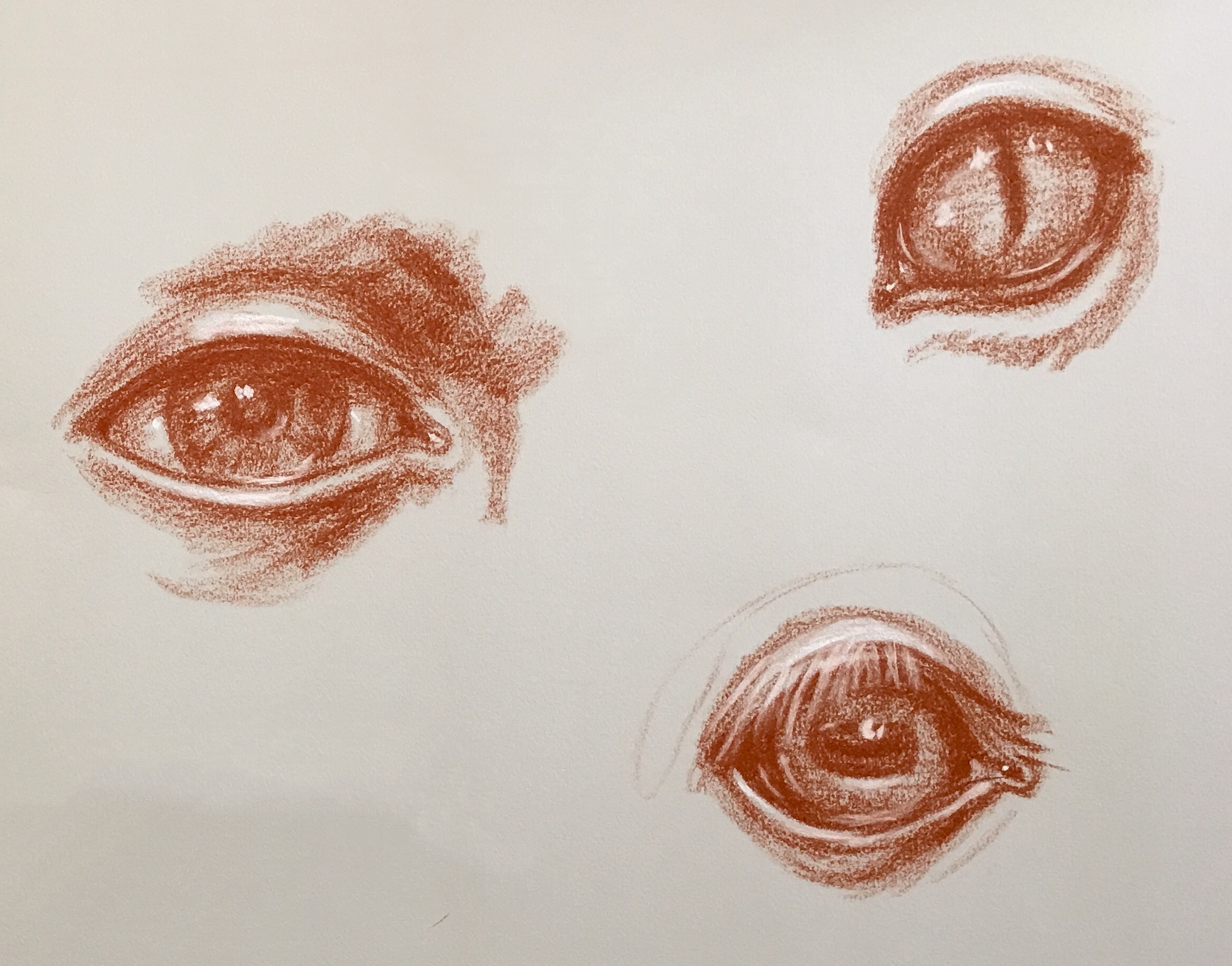

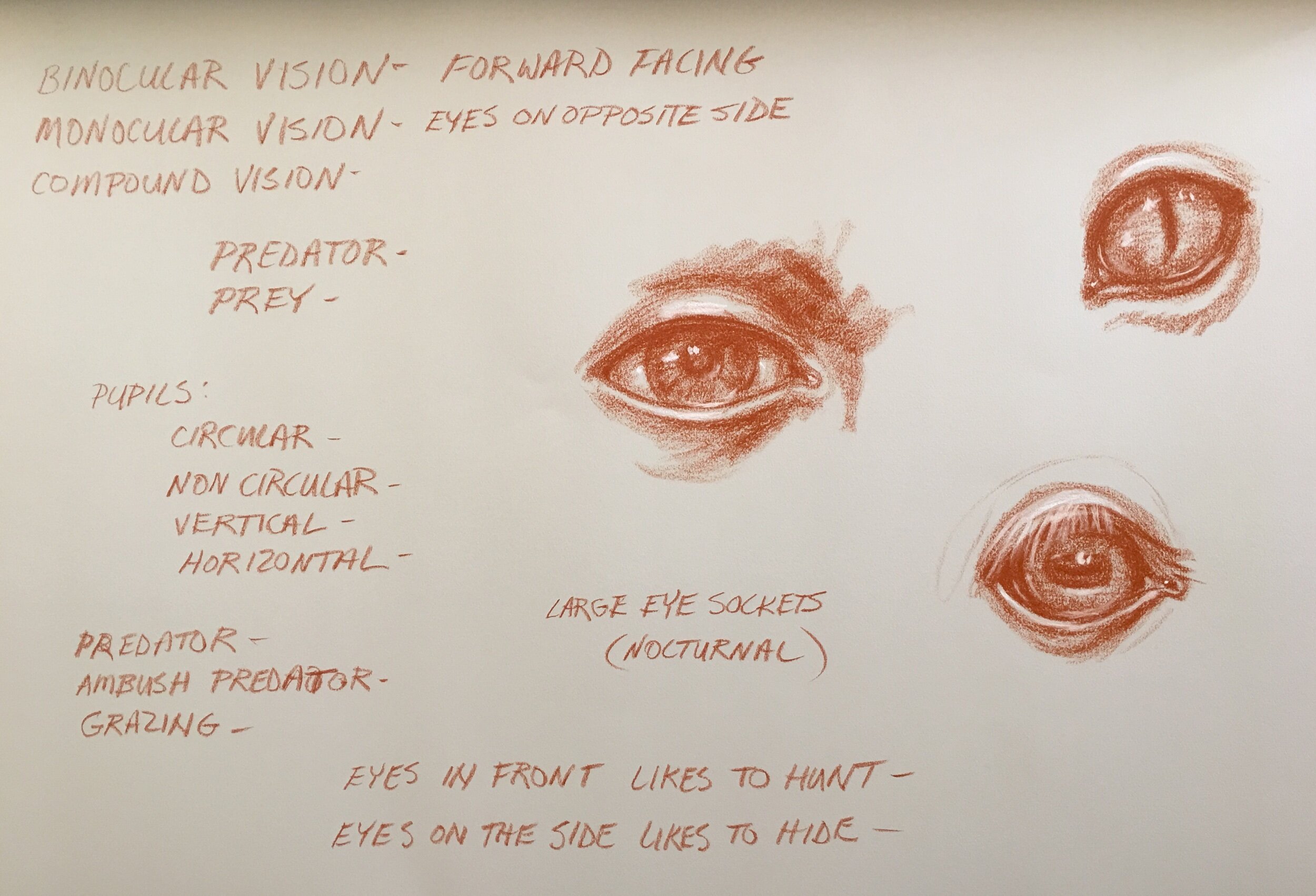

Écorché studies are primarily used in classical figure drawing and artistic anatomy training to enhance an artist’s understanding of the body's structure, volume, and function beneath the surface. By examining how muscles attach to bones and how they act in motion, artists can create more lifelike and dynamic representations of the figure, whether working from life, imagination, or memory.

Historically practiced by Renaissance masters such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, the écorché tradition remains a cornerstone of academic art training, bridging the disciplines of science and art to depict not only anatomical accuracy but also the expressive power and beauty of the human form.

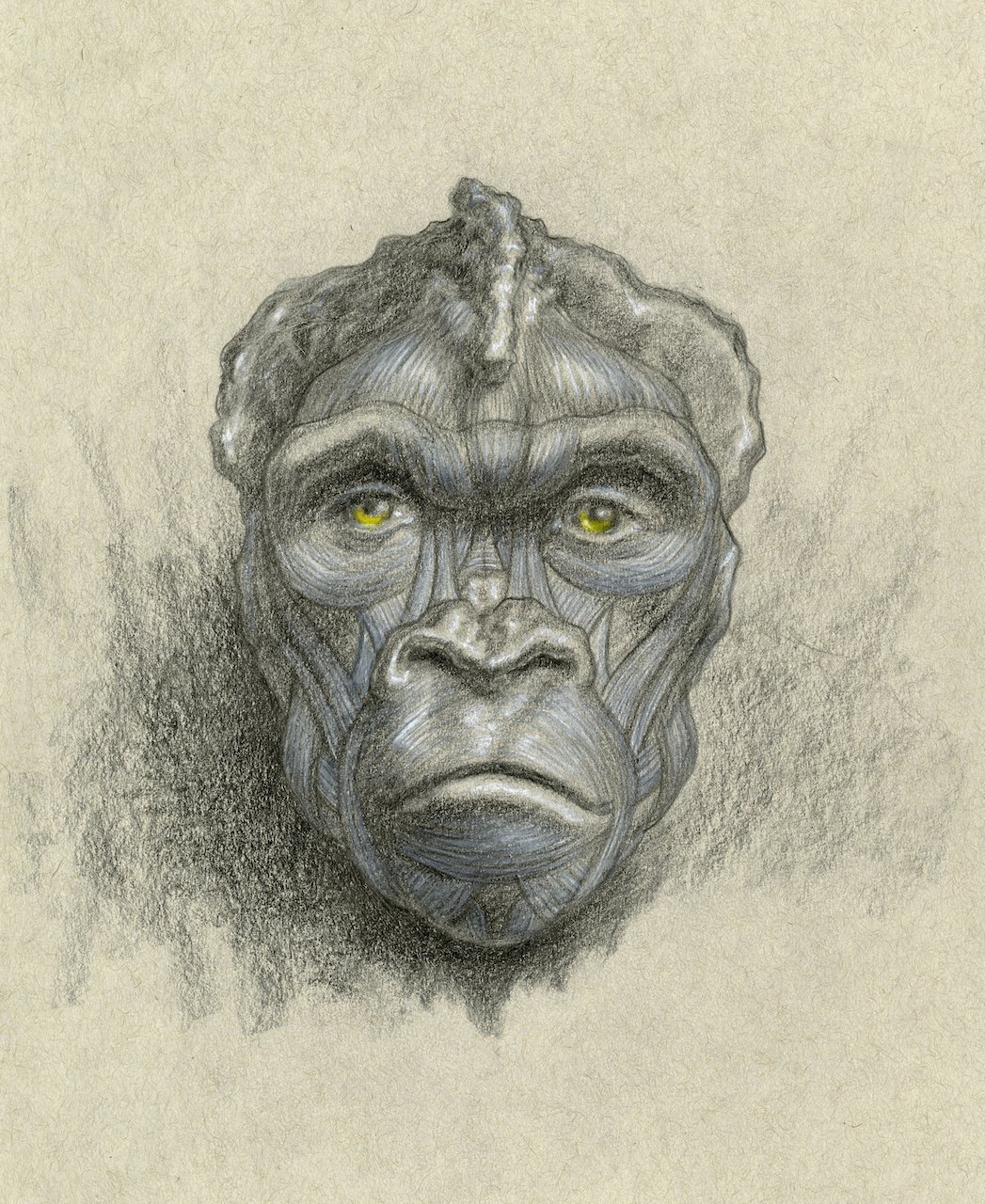

The term écorché, meaning “flayed” in French, refers to a figure drawn, painted, or sculpted with the skin removed to reveal the underlying musculature. While the word may evoke clinical detachment or anatomical morbidity, in the classical tradition of figure drawing, écorché is anything but sterile. It is, in fact, a profoundly poetic discipline, a merging of science and art, intellect and intuition, that allows the artist to render not only the body’s architecture but also the presence, emotion, and grace of the human spirit.

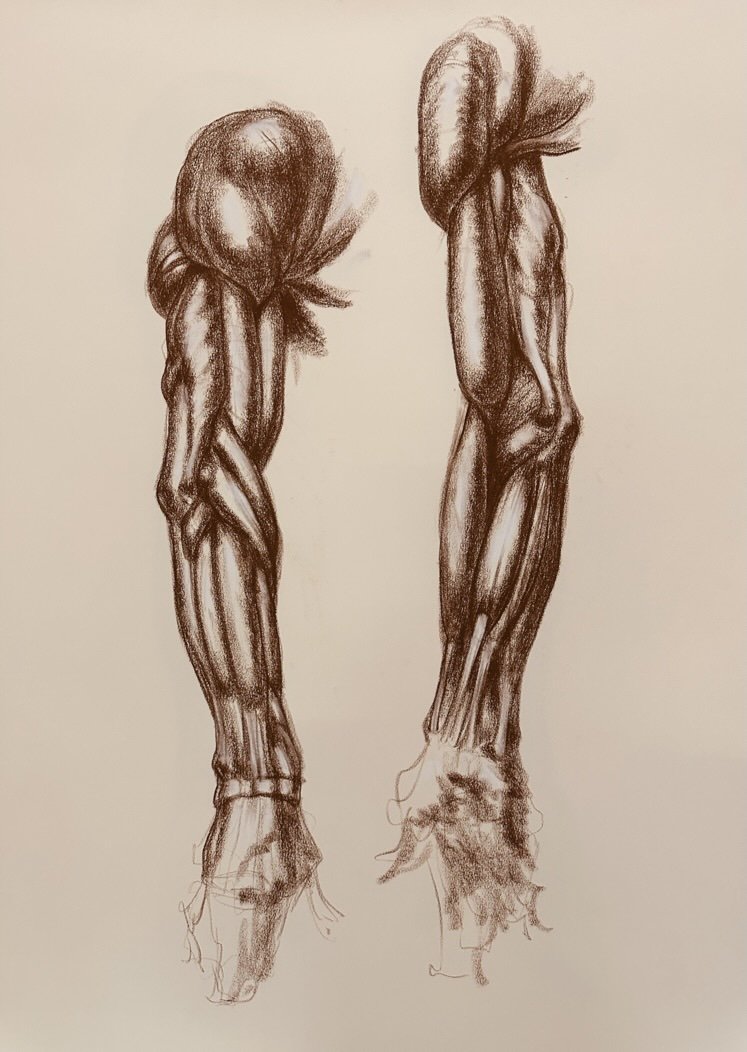

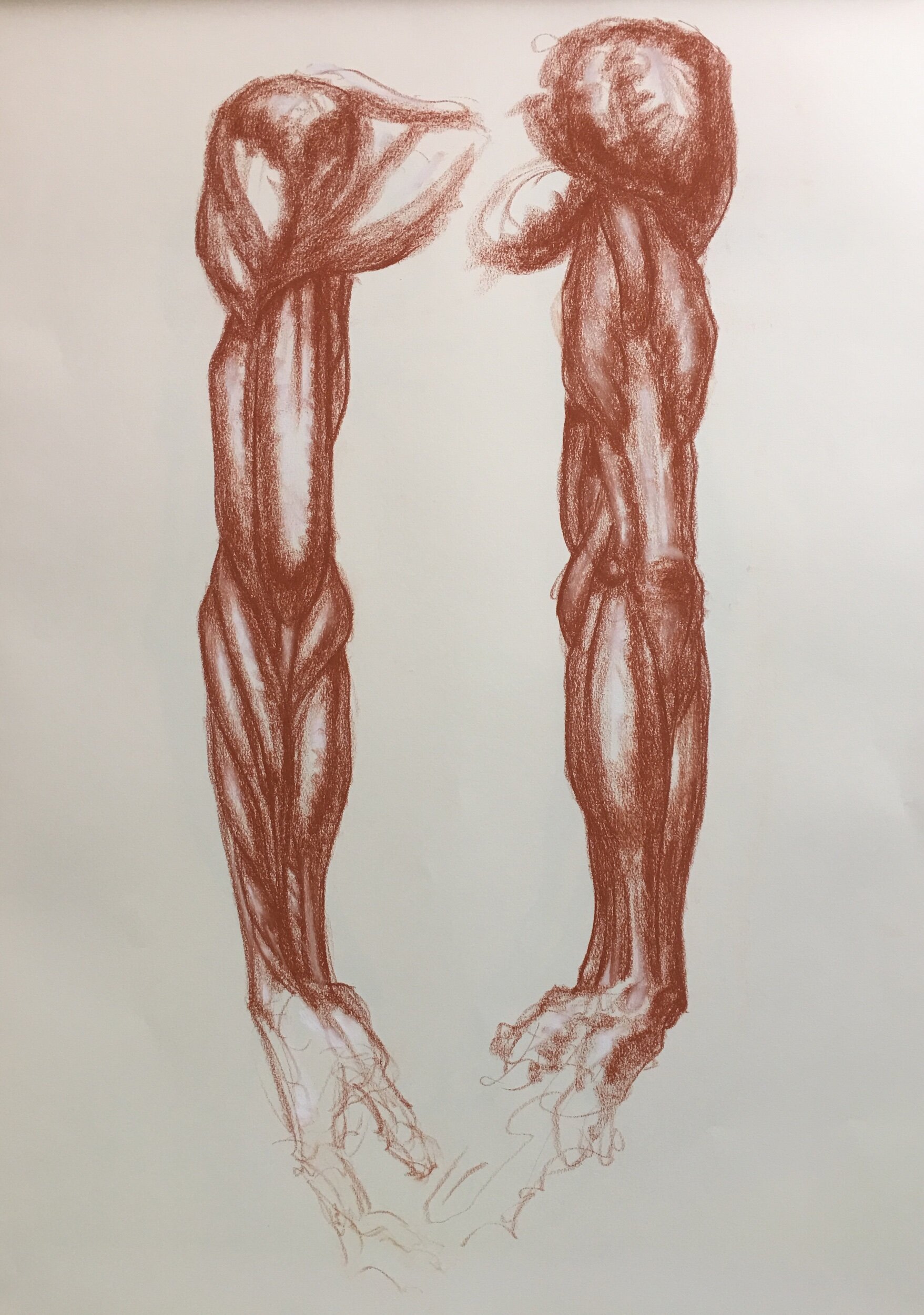

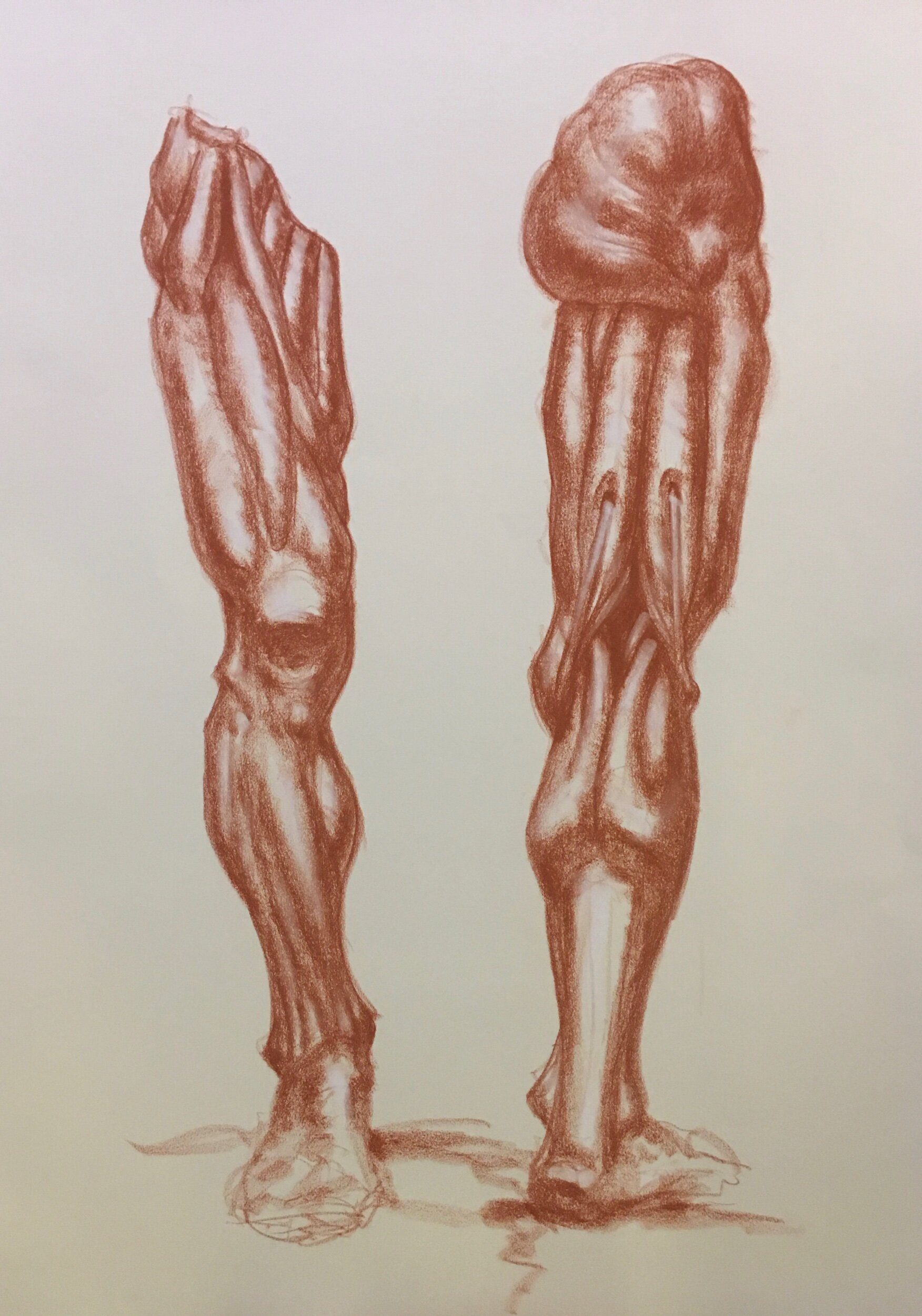

Historically, écorché has been a cornerstone of academic art training, dating back to the Renaissance, when artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Andreas Vesalius sought to understand the body from within. For these masters, the study of anatomy was not a secondary concern; it was essential to their work. By knowing the muscles, bones, tendons, and their interrelationships, artists could infuse their figures with authentic structure and expressive depth. The écorché method became the bridge between observation and understanding, between the living model and the imagined gesture.

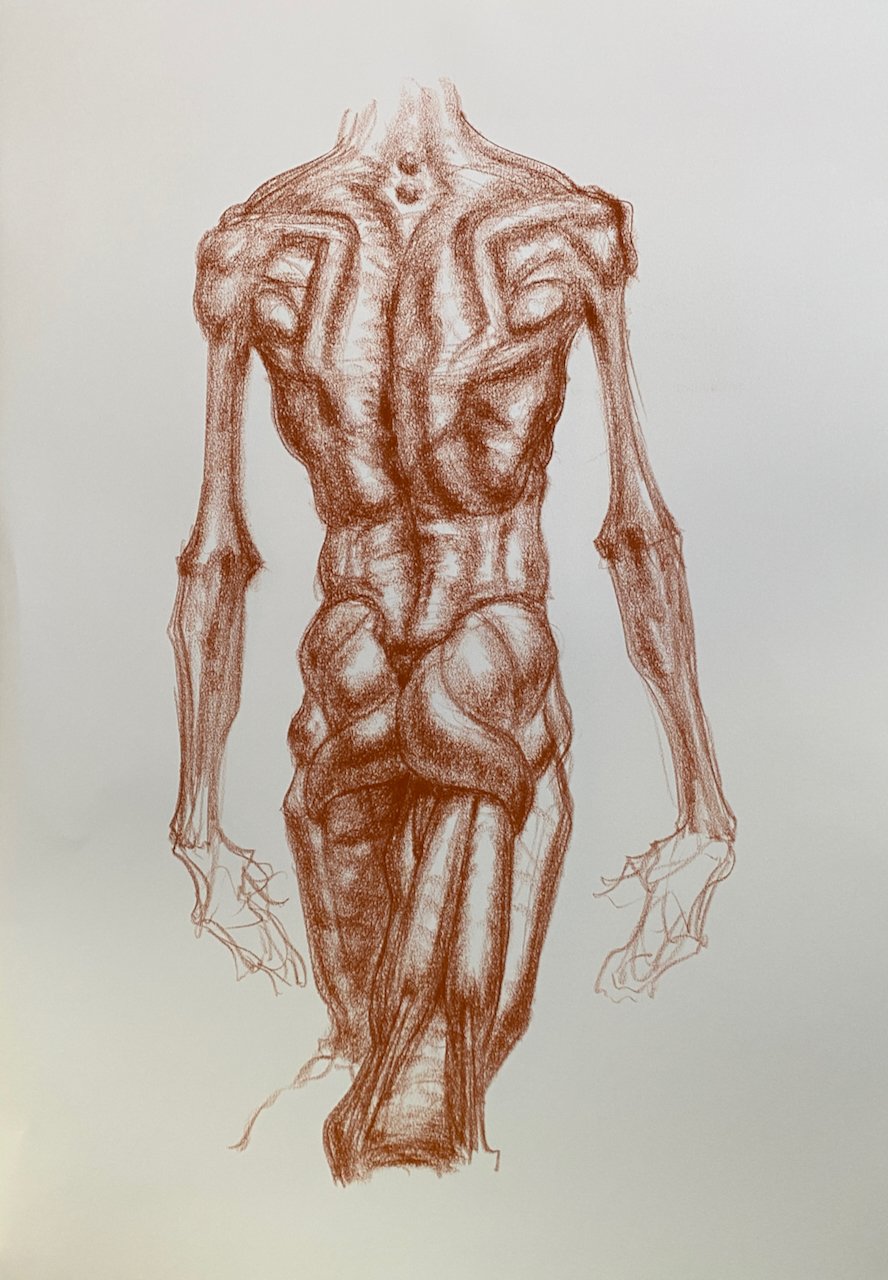

In the classical atelier tradition, where life drawing holds a central role, écorché is not approached as a cold diagrammatic exercise. Instead, it is an act of reverence: a visual meditation on what it means to be embodied. When drawing from life, the artist is confronted with the outer surface, the skin, the silhouette, the shadow, but écorché invites us to look deeper, to see not just what the eye perceives but what the mind knows to be true. It asks: What supports this pose? What tension or release lies beneath the surface? Where does movement originate, and where does it resolve?

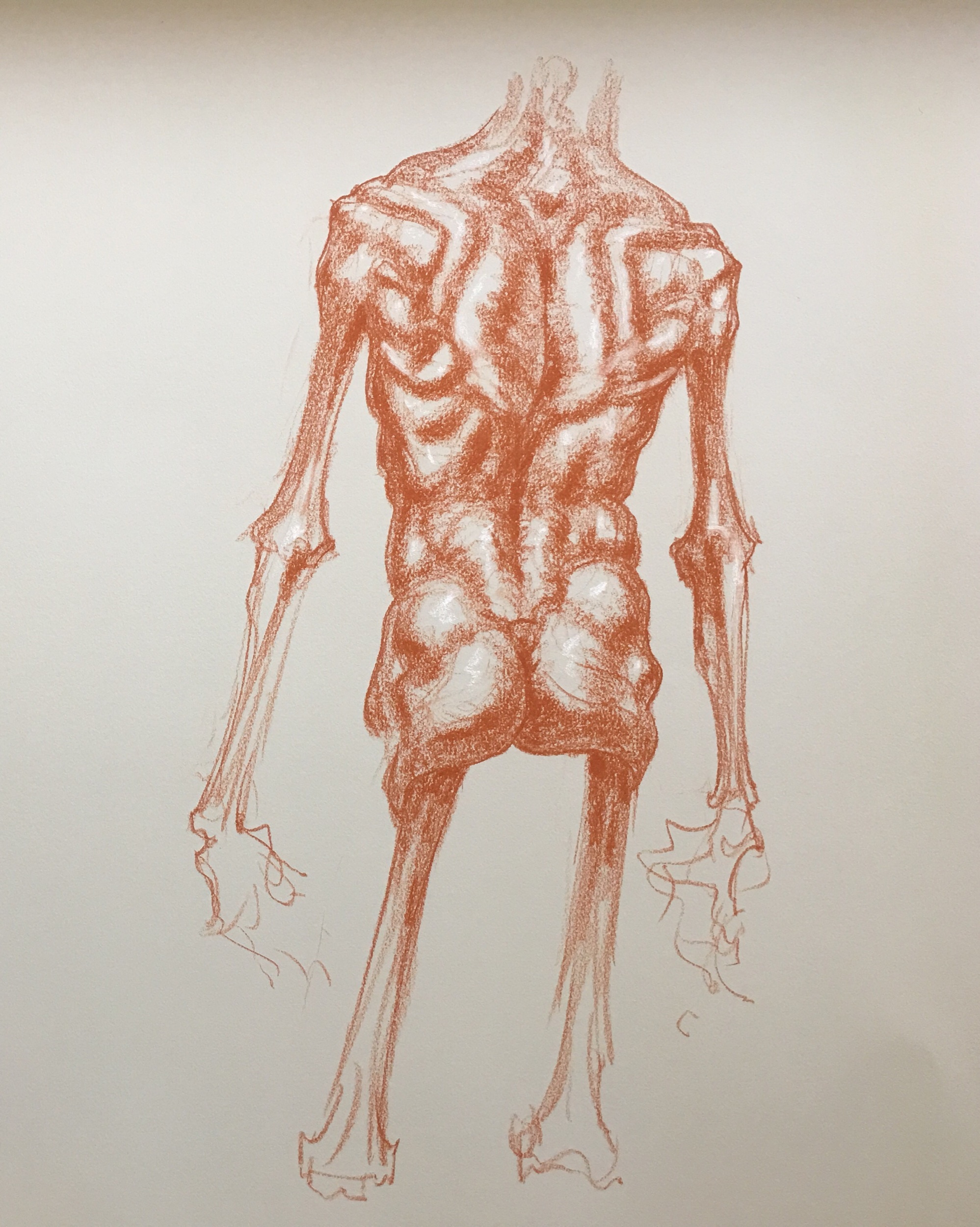

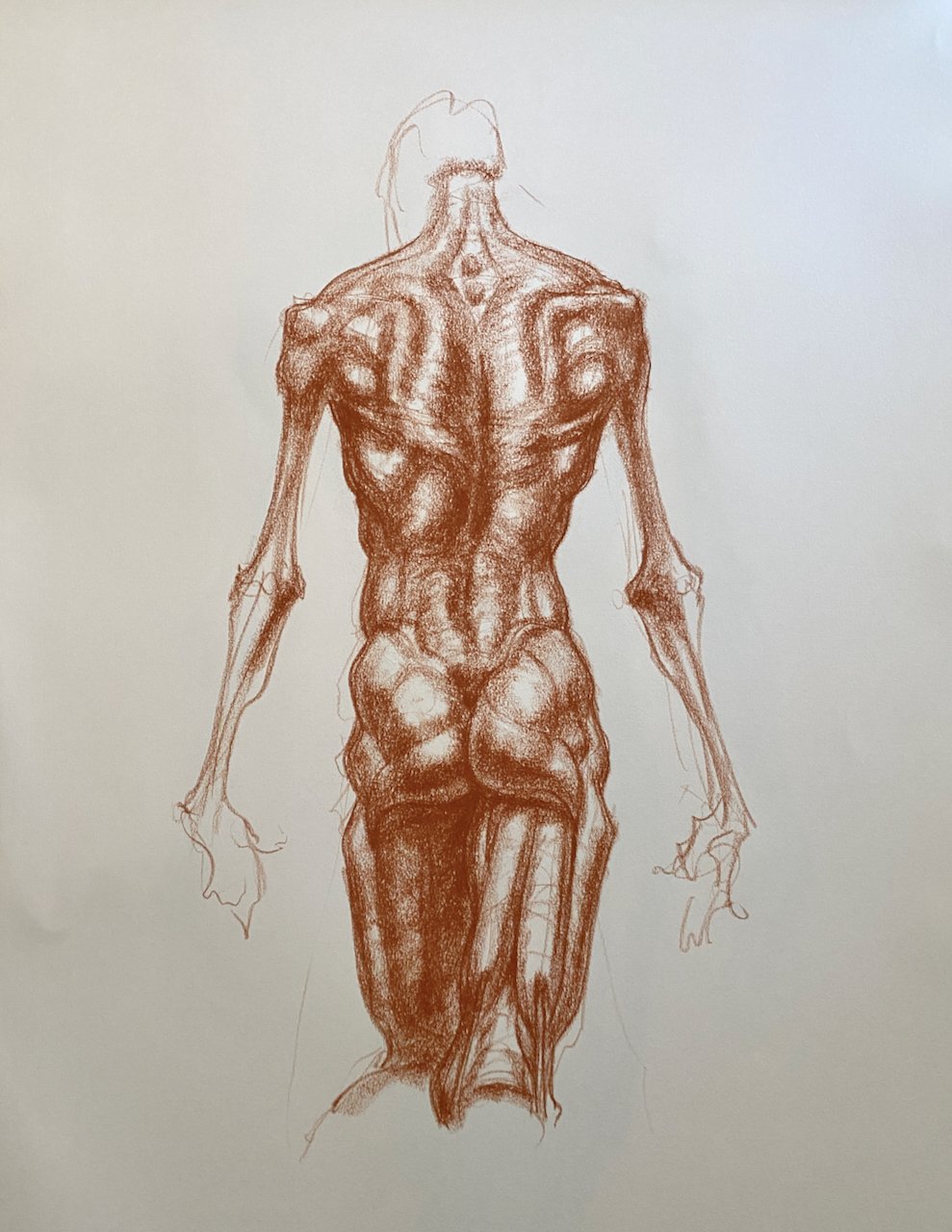

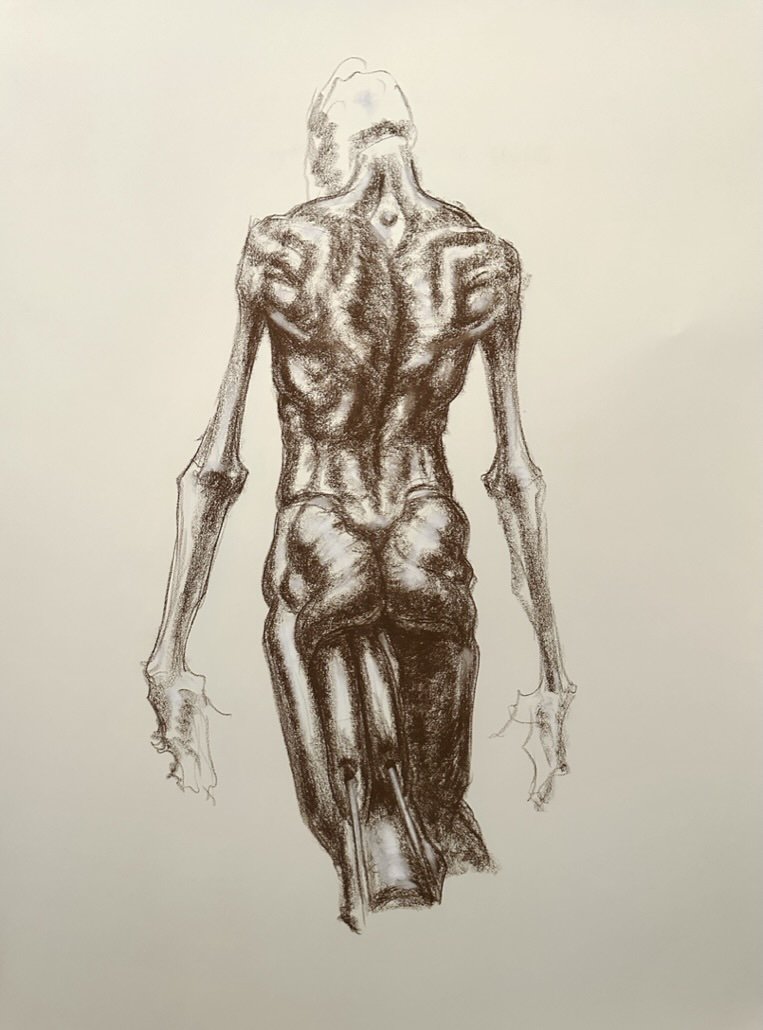

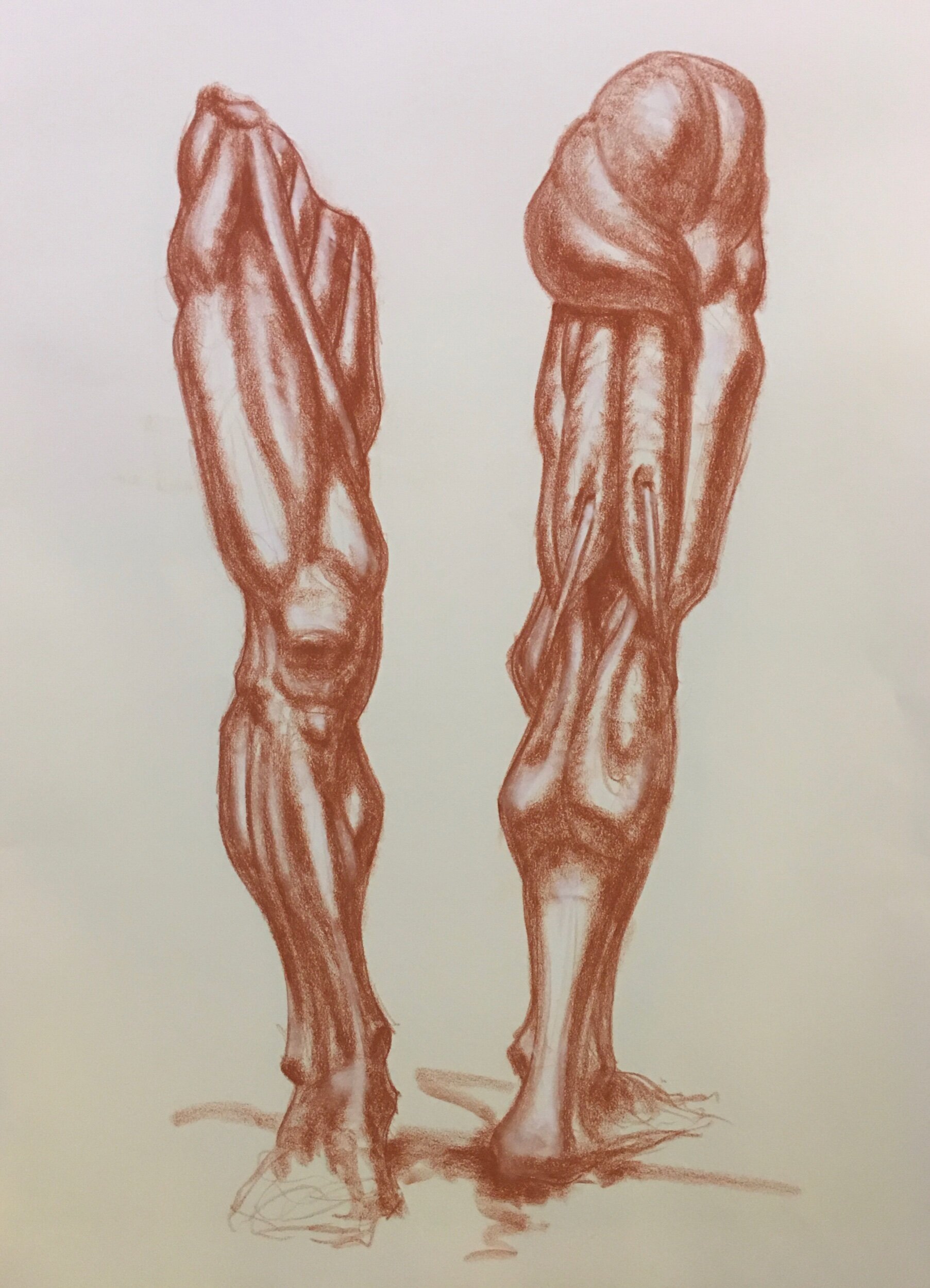

By internalizing the anatomical rhythms of the body, how the deltoid arcs across the shoulder, how the latissimus draws downward to the spine, and how the rib cage rotates against the pelvis, the artist becomes fluent in the language of form. This knowledge is not rigid or formulaic; it is alive, responsive, and interpretive. It allows for the creation of figures that are not merely correct, but compelling, figures that feel inevitable in their construction and graceful in their weight and gesture.

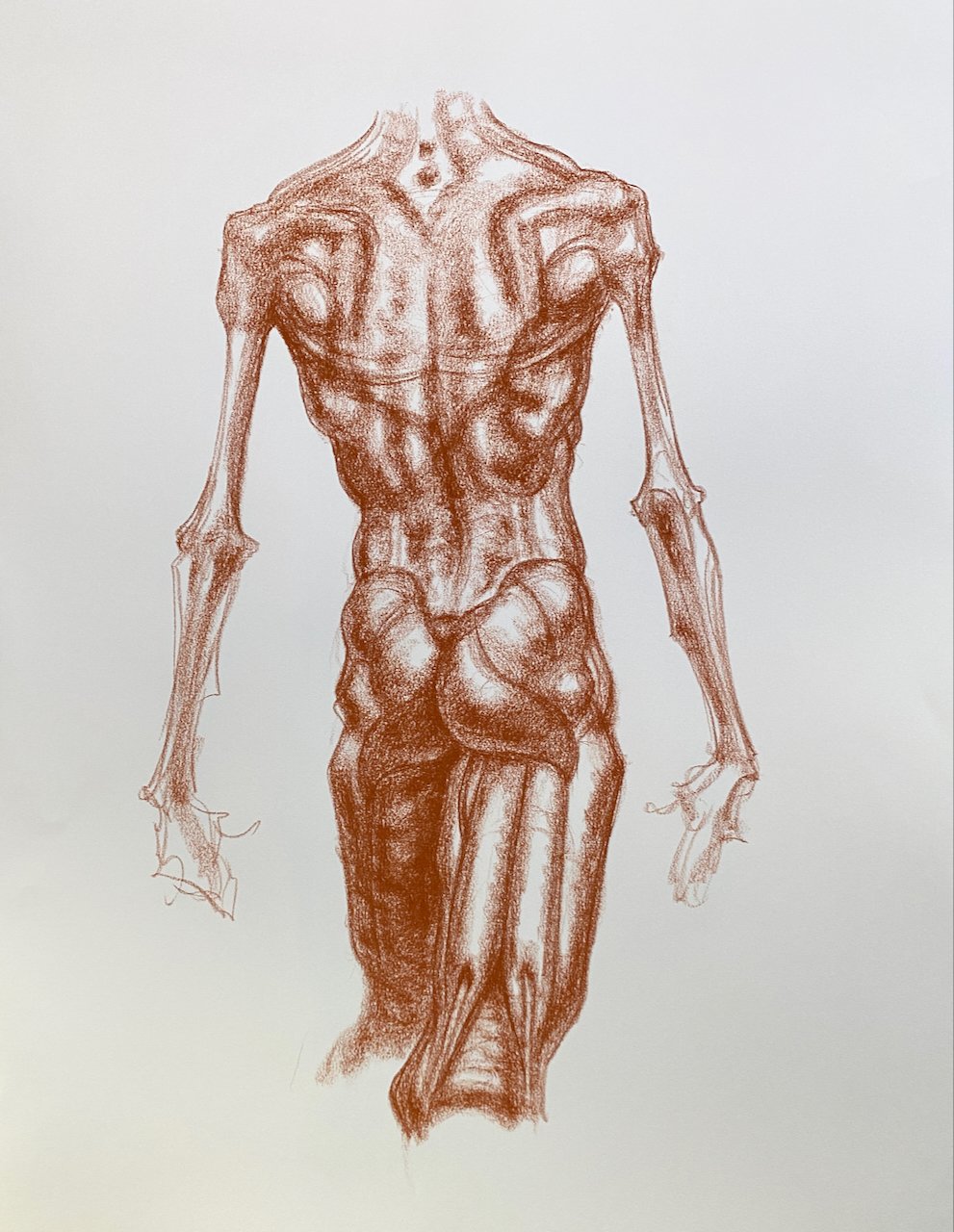

Écorché, then, is not just about anatomy; it is about essence. Through the study of form beneath the flesh, we begin to uncover the psychological and spiritual truths embedded in posture, proportion, and movement. The tilt of a clavicle, the stretch of an oblique, or the sag of a trapezius can speak volumes about a figure’s mood, age, emotion, or intent. In this sense, écorché becomes a vocabulary of empathy, an artistic tool for translating the human condition into line, volume, and light.

In life drawing, where poses are fleeting and the model’s breath defines the timing of the gesture, the artist trained in écorché can respond with clarity and purpose. Rather than copying what is seen, they interpret it, constructing the figure from the inside out, balancing accuracy with expressiveness. A turn of the torso becomes not just a contour to follow, but a dance of interlocking planes. A bent knee is no longer a guess, but a symphony of patella, femur, and quadriceps in action. The result is a drawing that breathes, not because it is finished to photographic perfection, but because it contains intention and integrity.

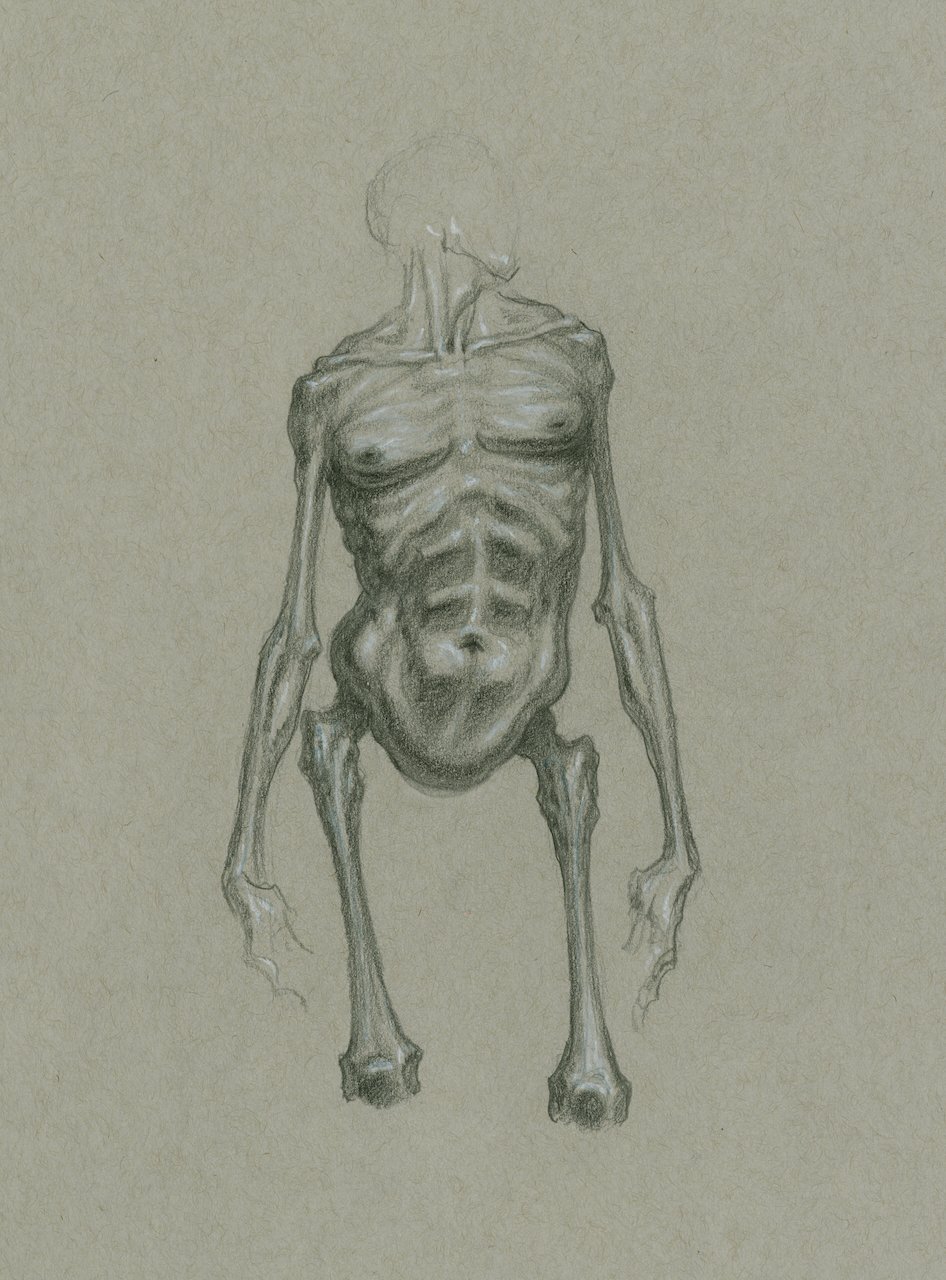

The power of écorché also lies in its aesthetic paradox: it is a study of the raw and exposed, yet it often yields images of sublime beauty. A flayed figure, when drawn with sensitivity and structure, becomes a portrait not of death, but of life in its most honest and unadorned form. The musculature, rendered with tension and subtlety, reveals the dignity of the body’s design, its capacity to carry weight, to reach outward, to fold inward, to endure.

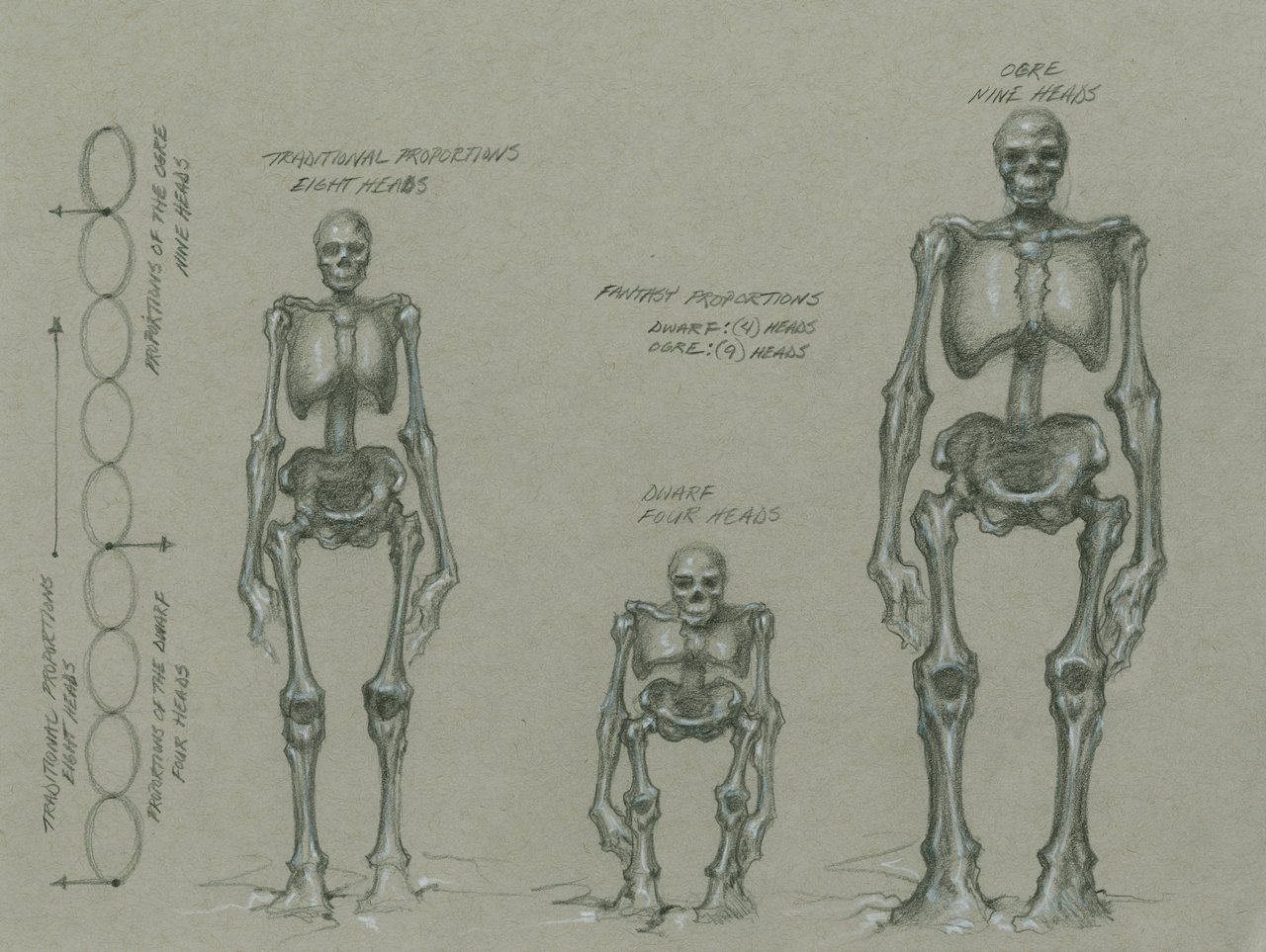

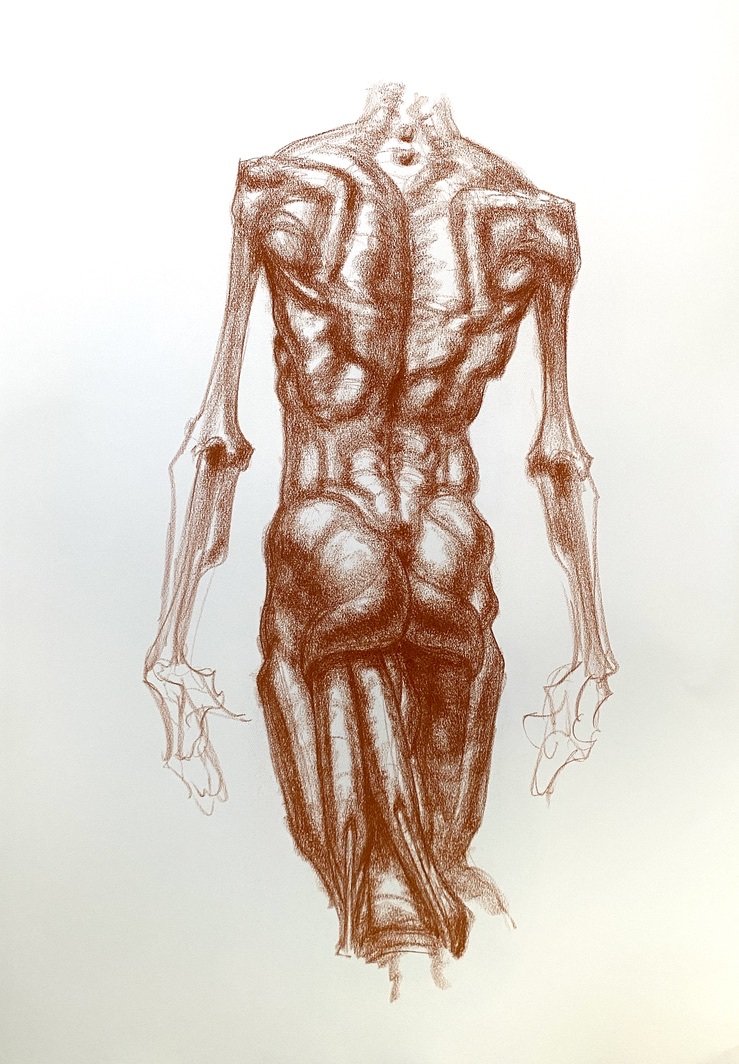

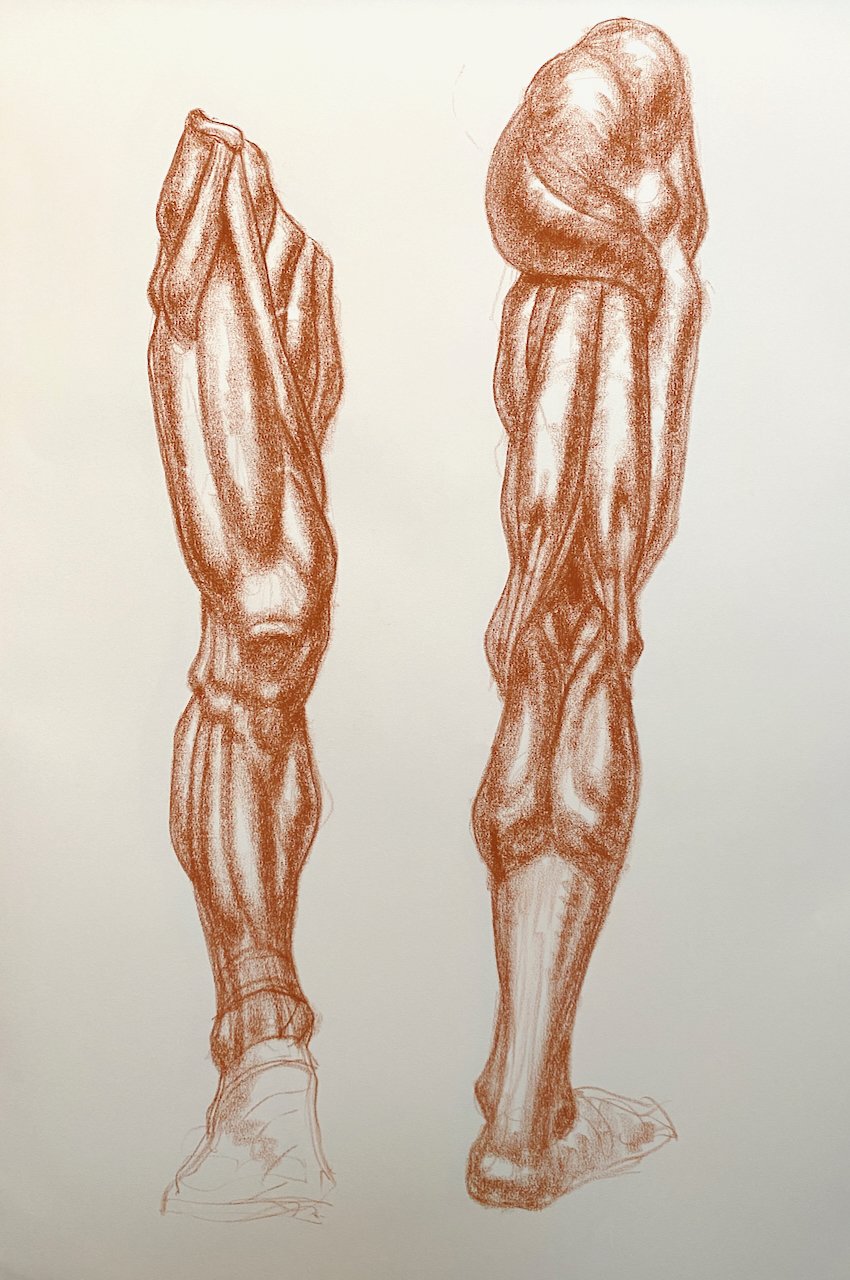

In my practice and teaching, I view écorché as both a discipline and a liberation. It disciplines the eye to observe more deeply, the hand to construct more confidently, and the mind to comprehend the logic of the body’s design. But it also liberates the artist from reliance on surface detail. When an artist understands the skeletal and muscular foundations of form, they can draw from imagination, invent poses, adjust proportions, and abstract with purpose.

This freedom is fundamental when the goal is not just realism, but expression. Classical figure drawing is not about replicating the human body as a static object; it is about conveying its spirit. The finest figure drawings, from the Renaissance to the modern atelier, are not prized merely for their detail but for their power: the ability to suggest weight, tension, stillness, or motion with a single flowing line. Écorché, far from being an obstacle to this expressive clarity, becomes its foundation.

Beyond the technical, there is also a philosophical resonance to écorché. To study the structure beneath the skin is to acknowledge our shared humanity. Regardless of gender, age, race, or appearance, the underlying anatomy unites us. It is the typical architecture upon which all our stories are built. In this way, the practice becomes a reflection on mortality, endurance, and the fragile strength of being human.

Moreover, in a time when digital tools and superficial visual trends often dominate the art world, the quiet, disciplined study of écorché offers something rare and essential: depth. It requires time, patience, and humility. It rewards not flash but understanding. It reminds us that the artist is not merely a recorder of appearances but a translator of truths, a maker of forms that embody life’s complexity and dignity.

A deep understanding of écorché empowers artists to breathe vitality and authenticity into their figure drawings. By studying the muscles beneath the skin, their origins, insertions, functions, and relationships, artists develop a profound awareness of how the human body moves, balances, and expresses emotion. Rather than relying solely on surface observation, the artist equipped with anatomical knowledge can interpret and reconstruct the figure with confidence and intention.

This internal comprehension allows the artist to transcend stiff, mannequin-like renderings. Instead of figures appearing frozen or overly posed, they begin to move naturally across the page, with rhythm and weight. Muscles stretch, contract, and coil with believable force; bones anchor motion and establish structure. The body becomes a living architecture of tension and release.

Through écorché, gestures are no longer a matter of guesswork; they are understood. The arc of a back, the twist of a torso, the lift of a shoulder, all become expressive tools guided by knowledge, not imitation. This results in figures that not only resemble human beings but feel animated by the very spirit of humankind: capable of grace, power, emotion, and purpose. Such mastery connects anatomical truth with artistic poetry, achieving drawings that pulse with life.

In conclusion, écorché is not an outdated academic exercise; it is a living, breathing practice that continues to inform and elevate the work of serious figurative artists. It deepens the artist’s connection to the subject, enhances their technical command, and opens a gateway to more profound expression. When approached with devotion, écorché is not just about drawing the body; it is about drawing what lies within: the structure, the spirit, and the enduring strength of humankind.